Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA

This article appears in West 86th Vol. 31 No. 2 / Fall–Winter 2024

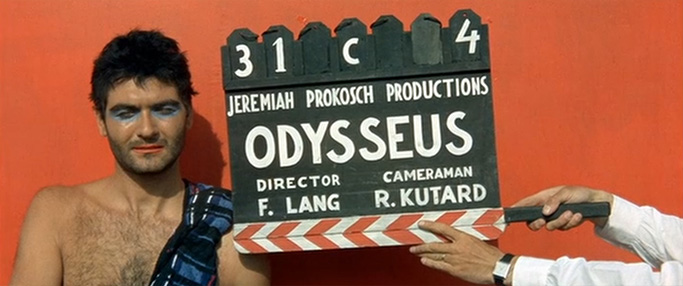

Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le mépris (Contempt, 1963) adapts Alberto Moravia’s novel Il disprezzo (Contempt, 1954) to tell the story of an unraveling marriage set against the narrative backdrop of a producer, scriptwriter, and director (Fritz Lang playing Fritz Lang) struggling to make a Technicolor movie of Homer’s Odyssey. In Lang’s mise en abyme, human actors made-up in vivid colors play Odysseus, Penelope, a centaur, and a Siren, while painted plaster casts of ancient statues perform as the Olympian gods and Homer. These painted statues intervene in long-standing debates about paint on sculpture and invoke the instability of commercial color film technologies to take aim at the fixed tradition of a monochrome classical past and the gendered, racialized associations that past had so often been designed to conjure.

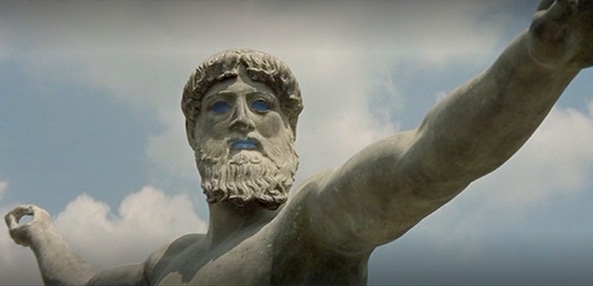

About ten minutes into Godard’s 1963 film, Contempt, one encounters the slow, monumental shots of the Greek gods. Filmed against a brilliantly blue sky, the sequence of classical statues sets off in the viewer a sense of shock and recoil. Onto the white marble, made harsh by intense sunlight, Godard has daubed patches of crude polychromy: blank cerulean eyes, garish red mouths, hair the color of mahogany. One is upset to be in the presence of a classicism made vulgar—and somehow implausible by color.1

So opens an essay published by art historian Rosalind Krauss in Art in America in 1974 in which—with the support of color photographs by Dan Budnik—she exposed the posthumous removal of paint from David Smith’s metal sculpture, an excision facilitated by one of the executors of the artist’s estate, the critic Clement Greenberg.2 In order to think through Greenberg’s acts of removal and the recoil produced by color in Smith’s sculpture, Krauss invokes the painted plaster casts of Greek statues that perform in Jean-Luc Godard’s film Le mépris (Contempt, 1963). While research on and exhibition of the vibrant colors of antiquity have only expanded in the fifty years since Krauss proposed a dubious universal discomfort with their vulgarity and implausibility, monochrome white marble sculpture remains a shorthand for the art of ancient Greece and its receptions.3 The painted statues in Contempt engage with debates about paint on modern sculpture that were unfolding alongside the film’s production in the mid-twentieth century. Contempt constructs a mode of classical reception shaped not by shared figural forms but by the shared transmedial practice of adding paint to sculpture.4 The visual arts play an important role in the film, and through their critical writings in Cahiers du cinéma (Notebooks on cinema) Godard and others sought to fit “the auteurs of films . . . definitively into the history of art.”5 While Godard’s work has often been situated within a discourse on painting, the performances of painted statues in Contempt, instead, translate across media to link painting, sculpture, and performance through a shared use of color.6 The film mobilizes and historicizes the instability of commercial color technologies to take aim at a fixed tradition of a monochrome classical past and the gendered, racialized associations it had so often been designed to conjure.7

Three moments shape the film’s mid-century perspective on color—the development of cinematic technologies, the twentieth century’s redeployment of antiquity, and antiquity itself. Among the best known of Godard’s critiques of the commercial film industry, Contempt adapts Alberto Moravia’s Italian “vulgar and pretty pulp fiction” Il disprezzo (Contempt, 1954) to tell the story of an unraveling marriage—of Camille Javal (Brigitte Bardot) and Paul Javal (Michel Piccoli)—set against the narrative backdrop of a producer, scriptwriter, and director (Fritz Lang played by Fritz Lang) struggling to make a Technicolor movie of Homer’s Odyssey set in the Cinnecittá Studios in Rome (“the modern world; the West”) and in Capri (“the ancient world, nature before civilization and its neuroses”).8 In this film within the film—Lang’s Odyssey—human actors made-up in vivid colors play Odysseus, Penelope, a centaur, and a Siren, while painted plaster casts of ancient statues perform both as the Olympian gods Poseidon, Athena, and Aphrodite and as the poet Homer (figs. 1–3). Framed by landscapes with their own bright colors, the statues of Lang’s Odyssey propose a relationship between figure, ground, and sky that technologies of reproduction often disconnect but that were also important to the visual reception of such objects in antiquity.9 Lang’s Odyssey, thus, serves as a set piece for the imbrication of coloristic media. Training several thematic lenses on the role of color in the film and its classical source material—translation across languages, media, and space; cast production as a locus for the erasure of color across time; and the contingencies of color in theory and practice—lays bare Contempt’s intervention in the history of color.

Translations

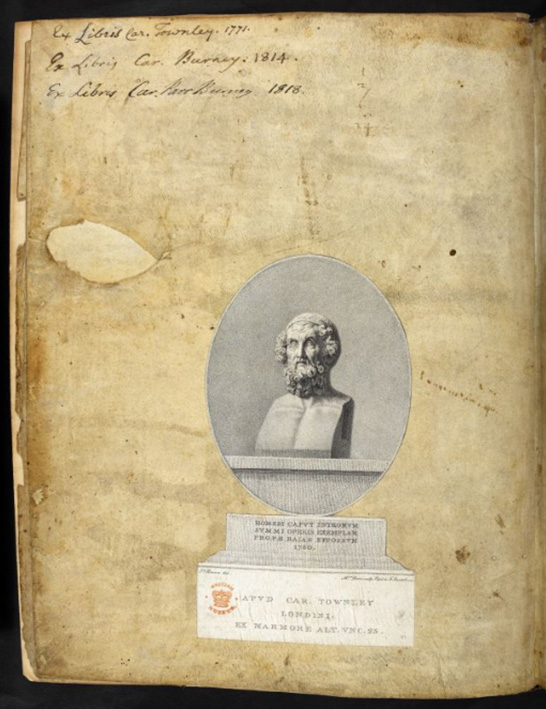

Performed, copied, cited, translated, and adapted for millennia, the Homeric epic poem the Odyssey offered Godard a framework within which to stage his own rhapsodic exploration of transmedial storytelling. The poem recounts the ancient Greek hero Odysseus’s long journey home across the Mediterranean from Troy to Ithaca after the end of the ten-year Trojan War, launched after Aphrodite trafficked Helen, the wife of Bronze Age–king Menelaus, to the Trojan prince Paris (fig. 4). Crafted through oral performance in the eighth century BCE, the Odyssey was written down in ancient Greek beginning in the Archaic period and copied and recopied over millennia onto papyrus, manuscripts, and printed books in Greek, Syrian, Arabic, Latin, and, eventually, into many modern languages and creative adaptations.10 The materiality of the poem itself has a rich history across languages and media, from embodied recitation to the printed book.

Ideas about translation tend to center the operations between two languages. While Contempt does thematize this mode of translation in the international world of commercial filmmaking, the film also incorporates translation between media and across space. Moravia’s novel, written in Italian prose, focuses on a screenwriter working on an adaptation of an ancient Greek epic poem. Godard’s multilingual project adapts Moravia’s text “as it is” (tel quel) into film, crafting an intermedial translation.11 The translation of the novel into film, a translation from one medium to another, shifts the relationship of the film within the film—Lang’s Odyssey—to the whole, a shift that Lang addresses directly in his verbal sparring with the American producer Jeremy Prokosch when he responds dryly to Jeremy’s critique that the script and the screen do not correspond by stating: “Naturally. Because in the script it is written, and on the screen it’s pictures.”12

Translation across languages also features in the film. Francesca Vanini, Jeremy’s multilingual assistant, moves between French, Italian, German, and English to translate for the group, at times summarizing or otherwise shifting the meaning of what was said in her reportage.13 While watching the daily takes of Lang’s Odyssey, the crew names each Greek god by their Roman counterpart—Venus (Aphrodite), Neptune (Poseidon), Minerva (Athena)—and the opening credits list Contempt’s production company as Minerva Productions, an early gesture to the film’s engagement with translation from Greek to Latin. In one scene, as Jeremy and Paul discuss payment for his revisions to the script, Camille flips through a book of color photographs of erotic Roman paintings, Jean Marcadé’s Roma amor (1961).14 Later, Jeremy enters the house carrying the same book:

Jeremy: Paul, I found a book of Roman paintings that I thought would help with the Odyssey.

Paul: Mais, l’Odyssée est grecque.

Francesca: Jerry, the Odyssey is Greek.

Jeremy: Yes, I know.15

Jeremy hopes that the book’s erotic polychrome Roman wall paintings will inspire Paul to produce a sexier, more sellable color Odyssey, and his dismissal of the distinction between Roman paintings and the Greek epic plays on the translation of the Odyssey into Latin and the citation of Greek art by Roman artists.

Building from this history of linguistic, cultural, and geographic translation, Godard sets the filming of Lang’s Odyssey not in Greece but in Italy, drawing on Vergil’s Latin reworkings of the Iliad and the Odyssey in the Aeneid, the entanglement of Greek and Roman visual art, and ancient and modern efforts to map Odysseus’s wanderings in the region (fig. 5).16 French politician and philhellene Victor Bérard and Genevan photographer Fred Boissonnas captured imaginations in 1912 by sailing and photographing the route that Bérard argued Odysseus had taken, connecting the Li Galli archipelago off Sorrento with the territory of the Sirens, “who bewitch all passerby” (Od. 12.39).17 British naval historian Ernle Bradford claimed to have heard the Sirens while stationed near the archipelago during World War II.18 Scenes of a swimming Siren in Lang’s Odyssey and of Camille swimming while Paul lounges on the rocks both build from the long association of this region with Odysseus’s encounter with the Sirens and forge a connection between Lang’s Odyssey and the larger narrative into which it has been set.19 Godard also shot part of Contempt at Sperlonga, an archaeological site up the coast discovered in 1957, just six years before Contempt was released, where the Roman emperor Tiberius filled a grotto with statues of scenes from the Odyssey and where Giuseppe de Santis shot his Neorealist film Non c’é pace tra gli ulivi (No Peace Under the Olive Tree, 1950), to weave together cinematic, archaeological, and ancient histories.20 The bright colors of the Italian coast have their own recursive histories and receptions that thematize geographic translations in and of the Odyssey.

Contempt’s color film captures the rich land- and seascapes of the Italian coast, which frame and encompass the film within the film. Shot through with brightly colored ekphrases, or vivid descriptions, of the different places through which Odysseus and his crew traveled, the variegated poetry of Homer’s Odyssey lends itself to color film. The colors of Lang’s Odyssey, thus, engage directly with the natural world, vibrant metals, stones, pigments, and textiles described with vivid language in the Homeric epic. These colors also tacitly refute long-standing debates over the presence or absence of such colors in Homer specifically and in Greek art more generally.21 Writing on Homer in 1858, four-time British prime minister W. E. Gladstone argued that ancient Greek–speaking people did not see or name color, suggesting that they were in some way color-blind.22 Colorless Homeric poetry, Gladstone argued, encompassed the “the original form and elements, in so far as they are secular, of European civilization.”23 Grounding his argument in his own textual translations of Homer, Gladstone did not engage with the visual arts and relied instead on hierarchies of the textual over the visual and performative. His text-driven account ignored growing material evidence for the many colors of and on ancient Mediterranean art and architecture presented to the public by antiquarians, artists, and scholars, such as John Gibson, Jacques Hittorf, Owen Jones, Franz Kugler, and Gottfried Semper.24

Despite the abundance of material colors used by artists in antiquity, much has been stripped away by time, wear, and technologies of reproduction, such as casts, prints, black-and-white photography, and film. These reproductions often circulate more widely and with fewer polychrome particulars than the objects that they reproduce. Paint on sculpture in particular has remained the most controversial locus of debates over color and classical antiquity. In contrast to reproductive processes that strip away color, Godard adds it back through filters, pigments, makeup, and shots tracking across land and sea. By staging these reproductions of polychrome ancient sculptures and brightly made-up actors, Godard refuses the monochrome ideal of the classical past that audiences might have expected and that earlier films had constructed. Although by the 1960s changes in film technologies had made color rather than black-and-white film the norm, in what was only his second color film Godard uses color on materials and objects that audiences expected to see in black and white. Refusing the trope of naturalism, Godard’s color does not make his statues more lifelike but makes his actors more like painted statues.25 Color’s instability—pictured through the partial coverage of each statue—plays into Godard’s long-standing engagement with an aesthetics of ruination, one that connects to the related instability of color in film.

Lang’s Odyssey brings the problem of color—a problem tied to reproduction—into dialogue with the frictions of translation, adaptation, and medium. Just as a white plaster cast might reproduce or translate a statue once rendered in a different material (e.g., bronze) or with additional colors (alloys, inlays, and additive pigments) and thereby emphasize shared forms across different materials, so might a film remake a poem already shaped by past performances, transcriptions, translations, and adaptations. Godard’s film and Lang’s Odyssey return to the performance origins of the epic now staged by both actors and statues. Color marks such transmedial operations and, Lang’s Odyssey proposes, traverses the linguistic, material, and performative.

Casts

Painted casts perform this translation of the Odyssey into film, and they are themselves a medium of translation. Casts are both the end of a process of citation and the beginning of a new network of associations and circulations, staging perpetual intermediality. Prior to still photography and film, casts were a primary means by which sculpture from antiquity circulated. They also served as an early subject of both black-and-white photography and film. Although we tend to think primarily about casts in the early modern and modern histories of reproductions of ancient Greek and Roman statues, ancient artists also produced casts.26 Due to the techniques of molding as well as their own monochrome white surfaces, casts contributed to the removal of color from statues and from perceptions of classical art. The addition of paint to the casts performing in Lang’s Odyssey highlights the role of cast-making in the subtraction of color from source statues and the relationship between casts and other technologies of reproduction, such as black-and-white photography and film, while also showcasing casts as the primary support for polychrome reconstructions.

A statue painted with a dark green patina and bright blue across its eye sockets and lips—two areas that would once have been polychrome on the bronze statue it reproduces—plays the sea god Poseidon (Neptune; fig. 6). The camera pans so that the statue seems to rotate toward the camera; its right hand is drawn back as if to throw an absent weapon, while its left arm extends forward, situating the audience as the god’s target. This painted cast cites an extant bronze statue discovered in 1926 in waters near Cape Artemision that is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens (NAM X15161). The narrator of Lang’s Odyssey identifies the statue, “And that’s Neptune, his [Odysseus’s] mortal enemy,” taking a position in debates over whether the statue depicts Zeus or Poseidon. While the film uses Poseidon’s Roman name, Neptune, highlighting one aspect of translation from Greek to Roman culture and language, the cast playing the god in Lang’s Odyssey cites a statue with strong ties to ancient and modern Greece. In 1953, a decade before Godard shot Contempt, the bronze was popular enough that the Greek government gave a bronze cast of it to the United Nations in New York (UNNY129G), where it remains on view in the lobby.27 Although now well known, due to its discovery in the early twentieth century, this statue did not shape eighteenth- and nineteenth-century ideas about ancient Greek sculpture or populate historical monochrome cast collections, an absence that Godard’s choice to cast this twentieth-century discovery in Lang’s Odyssey underscores.

The painted cast performing as Athena (Minerva) receives similar treatment without the painted patina (fig. 7). Its vacant eye sockets and lips are painted not blue but red, a distinction that marks Athena and Poseidon’s opposing sides in the Trojan War and throughout Odysseus’s long journey home following the war’s end. This Athena evokes a Roman marble statue of the goddess now in Paris (Louvre Ma 130) that may also cite an earlier bronze iteration with intact inlaid eyes found in 1959 in the Piraeus (Piraeus Archaeological Museum 4646).28 Ancient artists produced many different statues of Athena, most famously the Athena Parthenos, a colossal gold and ivory statue that once stood inside the Parthenon in Athens, images of which were cited widely.29 In that sense, reproducing a painted statue of Athena in Lang’s Odyssey both fulfills narrative demands and also invokes deep histories of reproduction and transmedial citation.

At the apex of a triad of three female-presenting statues in a field of red poppies stands a painted cast of Aphrodite of Knidos, the first naked statue of the goddess from Greek antiquity (fig. 8).30 Sculpted from marble in the fourth century BCE by Praxiteles and possibly modeled on his partner, a famous elite sex worker named Phryne, this statue broke with the visual tradition of a draped Aphrodite to depict her naked as if stepping from a bath. While Praxiteles’s statue is no longer extant, it was already famous in antiquity and reproduced many times, becoming a touchstone in the history of female nude.31

Among these citations is the Medici Venus, produced for the Roman Emperor Trajan’s baths, purchased in the sixteenth century by Alfonso d’Este, sold to the Medici family (inventoried in 1623), stolen from Rome by Napoleon in 1802, displayed in Paris, and repatriated in 1816 to Florence (Uffizi 1914 no. 224), movements that map intersecting financial and geopolitical stakeholders. None remains extant, but eighteenth-century viewers noted the Medici Venus’s gilding, a choice that aligned with Homer’s epithet of “golden” for Aphrodite. The gold-painted pubic hair and coiffure of the central Aphrodite in Lang’s Odyssey riff on this history.32

This gilded central figure looks over her left shoulder away from another painted cast draped in a blue chiton that leaves one breast and rouged nipple exposed and toward the reproduction of another Aphrodite at the right vertex. Naked, headless, and missing the majority of her arms, this white plaster cast has been painted with red nipples and a brown pubic triangle with a blue chiton bunched at her left side.33 Although its complete nakedness and headlessness differs, the cast’s missing arms recall another Aphrodite, a marble statue crafted in the second century BCE and found without its arms by a farmer on the Greek island of Milos in 1820. Now in the Louvre (Ma 399), the Venus de Milo has been widely reproduced in cast collections and reworked by later artists since its discovery, including Yves Klein’s painted plaster Blue Venus (ca. 1961).34 The painted triad in Lang’s Odyssey counters a whitewashed history of the female nude and engages those who courted controversy by incorporating color.

The poppy-filled landscape in which the trio are set up layers cinematographic and painterly allusions, foremost to Jean Renoir’s color film Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (Picnic on the Grass, 1959) and the Impressionist tradition he tracks in that film.35 Renoir’s film cites a series of paintings of the same title by different French artists—Manet (1863), Monet (1865–66), Cézanne (1876–77), his father, Pierre-August Renoir (1893), and, contemporaneous with Jean Renoir’s and Godard’s films, Picasso (1959–62). The elder Renoir set classicizing nudes in brightly colored landscapes, and Jean Renoir evokes these painterly scenes in film.36 These citations linked the elder Renoir’s anxieties about “chemistry’s role in creating an artificial, more vulgar society, in which appearances were seldom reliable,” with similar anxieties of filmmakers working with color technologies.37Godard’s citation of Renoir in Lang’s Odyssey not only reworks these visual fields but also evokes the history of color and technology embedded in the earlier paintings and Renoir’s film. With these transmedial translations, the film within the film draws together painterly, sculptural, and cinematographic resonances.

The triad of female-presenting casts in Lang’s Odyssey also resonates with Bardot’s opening scene as Camille in the film’s superstructure, in which she appears naked under a series of color filters and asks her husband to affirm his love for each body part.38 In disassembling her own beautiful body into its constituent parts, Bardot as Camille gestures to a tradition about ancient Helen of Troy recorded in accounts by Cicero (Inv. rhet. 2.1–3) and Pliny (HN 35.36) that the Greek painter Zeuxis (fourth century BCE) struggled to paint her extreme beauty and turned, instead, to an assemblage of body parts from five different girls. Bardot’s Camille reverses Zeuxis’s assemblage, narrating, instead, her own fragmentation—feet, knees, ass—reassembled into a monochrome whole through the different colored lenses—red, yellow, and blue—trained on her flesh.39 Here the work of Godard’s colors in the superstructure of the film intersects with the work of the colors of Lang’s Odyssey and specifically the painted, naked Aphrodite, the goddess whose human counterpart is Helen. Given the feminization of color, however, these painted Aphrodites draw attention to an ambivalence about color in Contempt, as it intersects with capital and the commodification of women, something that Bardot’s role as the larger film’s Hollywood Helen also charted.

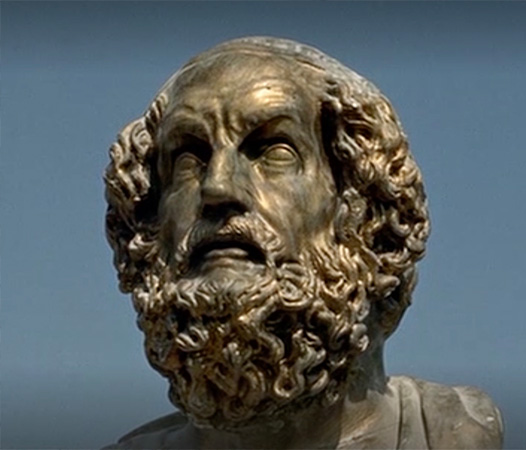

A gold-painted plaster portrait bust plays Homer, and so the poet appears in the film adaptation of his own epic poem rather like the cinematographer Coutard, who appears behind the camera in the opening credits of Contempt, and Godard, who appears in the closing scene of the film as Lang’s assistant (fig. 9).40 The bust’s metallic paint recalls bronze statues, although this image of Homer, with a receding hairline of curls, full beard, and solid surfaces over both deep-set eyes, is known only from extant marble iterations and likely reproduces a white marble portrait bust found in 1780 at Baiae in the northwest of the Bay of Naples (BM 1805,0703.85).

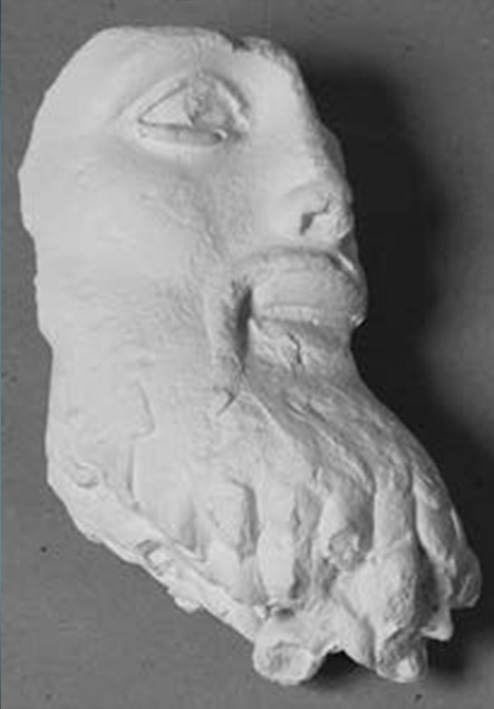

Although plaster casts are more typically associated with modern reproductions, such as Godard’s, ancient artists also produced casts, and Baiae was the site of a Roman cast production workshop in antiquity (fig. 10).41 Excavations in the mid-twentieth century (beginning in 1941) uncovered more than four hundred gypsum fragments, many of which seem to have been used to produce marble copies of Greek statues crafted in bronze in the fifth tofourth centuries BCE, a laborious and time-consuming technical process.42 Examining plaster cast pieces from this workshop, Gisela M. A. Richter noted that when casting an iteration of a bronze statue into plaster, ancient Roman artists transformed the different parts of the eye and lashes into an undifferentiated, monochrome form.43 While the bust of Homer’s solid and expansive eye sockets has typically been interpreted as the artist’s attempt to represent the poet’s reported blindness, such solidity also responds to a problem produced through techniques of reproduction that transformed the pieced-together material colors marking the different parts of an eye into a solid, white surface. The legacy of this practice persists in the solid, undifferentiated surfaces of the eyes of many extant portrait busts.44

In addition to the archaeological evidence from Baiae’s cast workshop, textual evidence from multiple sources affirms that ancient Greek and Roman artists produced plaster reproductions by making molds from existing statues. In his treatise Peri lithon (On Stones), the philosopher Theophrastus (fourth century BCE) describes different types of gypsum (ancient Greek gupsos, which could be translated as chalk, plaster, or cement), from Syria and the Phoenician coast to the region of Mount Athos, Thessaly, Cyprus, and in Magna Graeca along the Tarentine Gulf, sketching a wide range across which different types of plaster could be found (Peri lithon, 64–67). In describing the material’s various uses, Theophrastus emphasizes the importance of gypsum for taking impressions.

In Lucian’s Zeus Tragoidos (Zeus Rants) from the second century CE, the author plays casting practices for comedic effect, suggesting that some of the ambivalence about the status of casts (copies) common in modernity also had roots in antiquity. Rather like the assemblage of painted statues playing the gods in Lang’s Odyssey, Lucian presents the god Zeus assembling statues of gods from across the Mediterranean in various materials—bronze, marble, gold, and ivory. Zeus debates the appropriate ranked seating arrangement (by value of material, scale, or artistic skill) and the challenge of communicating across the group’s many different languages (“with the hands,” suggests Hermes).45 Zeus then speaks to a statue of Herakles about a bronze statue of Hermes, describing it as “the one defiled with pitch [pissa] from daily molds made by the sculptors” (Iupp. trag., 33). The bronze statue of Hermes then laments his pitch-covered state, blaming the bronze-workers who covered him with it and added a ludicrous corslet (a mold) to take their impressions.46 Lucian presents this mold-taking as humiliating for the bronze statue by emphasizing the mess, the touch, and the feminized dress of the mold. The comic value of the pitch-covered bronze statue of Hermes relies on the visible impact that taking molds has on objects—leaving residue and stealing surface traces. By casting painted plaster casts as the characters of the gods and Homer in Lang’s Odyssey, Godard participates in a long tradition of mold-taking and cast-making, including drawing on elements of humor and debasement that cling to such reproductions.

On a more somber note, casts reproduce not only statues but also traces of people through their connection to life-casting and death masks.47 The polychrome casts in Lang’s Odyssey build from this nuanced history of making casts through a dialogue with Roberto Rossellini’s black-and-white film Viaggio in Italia (Journey to Italy, 1954), posters of which adorn the walls and marquee of the theater in Naples in which Godard’s characters gather.48 As has been observed, Contempt has basic similarities with Rossellini’s film, which also features a marriage unraveling in the Bay of Naples amid Homeric associations and objects from classical antiquity, with the vivid distinction being Contempt’s color.49

Deep into Rossellini’s film, when the central couple, Alex and Catherine Joyce, have agreed to divorce, the caretaker of their Uncle Homer’s villa appears to take them to Pompeii to see the archaeologists “make a cast of the hollow space that has been left in the lava by a human body!”50 At the site, they watch this process of casting the space left in the ground by incinerated corpses. In a typical excavation, the archaeological reveal involves scraping away earth to expose ancient objects; here the archaeologists’ trowels and brushes reveal, instead, two newly made white plaster forms. These casts solidify the empty spaces once filled with bodily flesh (fig. 11). Gendered and coupled by the heteronormative imagination of the archaeologists who identify the two emerging forms as a man and a woman, perhaps a husband and wife, this macabre sight overwhelms Catherine, who rushes off in tears followed by Alex. Together, they thread their way through the site, and the camera follows them over intact stone roads and past remnants of painted walls. The same eruption of Vesuvius that killed so many people also preserved the vivid colors of Pompeii, but these are muted by Rossellini’s black-and-white film and by the monochrome plaster casts that stand in for the dead. Godard’s vibrantly painted casts of the gods in Lang’s Odyssey, in contrast, transform the unpainted white plaster casts of Pompeii’s dead in Rossellini’s film, intervening not only in the traditional, fossilized picture of classical antiquity but also in the picture of that antiquity in past films.

In one iconic scene in Journey to Italy, Catherine visits the Archaeological Museum in Naples.51 The camera tracks her encounters with ancient statues, filling the frame with the statues’ intact inlaid eyes so that they look directly at the audience. Rossellini’s emphasis on the sculptural gaze shot in black and white contrasts with the bright blue-and-red painted eyes of the gods that stare at the camera in Lang’s Odyssey. While Rossellini selects statues from Herculaneum, whose fitted-together inlaid eyes remain intact, Godard reproduces classical or classicizing statues whose inlaid eyes are now lost or have been blanked over in plaster or marble, and he fills in the whole space of the eye with blue or red paint. While black-and-white photography and film register but flatten out material and polychrome difference, the swaths of color in Contempt highlight the cast’s polychrome particulars by refusing the uniformity of a monochrome surface.

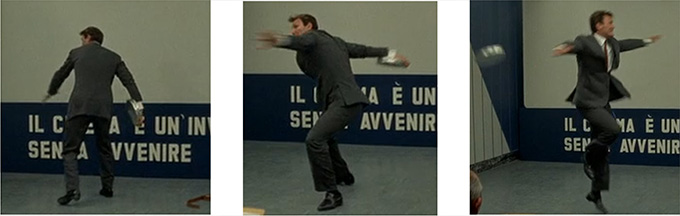

In Journey to Italy, the museum guide identifies one of the statues that Catherine (played by Ingrid Bergman) encounters from the villa of Herculaneum as “a discus-thrower. A Greek.”52 This misattribution—the statue depicts a runner—allows Rossellini to contrast the polychrome bronze statue in his film with monochrome white marble and plaster iterations of a lost bronze discus-thrower (Discobolus) sculpted by the Greek artist Myron.53 Godard responds to Rossellini’s Greek discus-thrower in living color, staged not through painted casts but through the body of the American producer Jeremy Prokosch (fig. 12). Unhappy with the direction of Lang’s adaptation, Jeremy leaps from his chair in the screening room and knocks the stacked reels of film to the ground. Grabbing one reel from the floor, he swings it discus-style toward the seating area and lets it fly. In the face of Jeremy’s tantrum, Lang comments dryly: “Finally, you get a feel for Greek culture.”54 Godard casts this agent of Hollywood and global capitalism as the discus-thrower, producing an embodied iteration of the famous statue that draws on an earlier reference likely active for both Rossellini and him.

In her black-and-white propaganda film documenting the 1936 Olympic games in Berlin, Olympia (1938), Leni Riefenstahl staged a naked male statue of a discus-thrower turning into the body of Hitler’s Aryan athlete (Erwin Huber), mobilizing myths of philhellenism, mimesis, and idealized naturalism to move from marble statue to living body in a frame (fig. 13).55 The monochrome white marble Roman statue in Riefenstahl’s film reproduced an earlier ancient Greek bronze statue by Myron that is no longer extant but that was reproduced repeatedly in antiquity. Riefenstahl filmed a plaster cast of the Discobolus already in Germany, releasing Olympia just a month before Hitler purchased an ancient Roman marble copy, the Lancellotti Discobolus, in Rome on May 18, 1938, to display it in the Munich Glyptothek.56 Repatriated after the defeat of the Third Reich, the statue remains on display in the Palazzo Massimo (126371) in Rome. In contrast to the white plaster staging of Riefenstahl’s film, Rossellini stages Bergman encountering a Roman polychrome bronze discuss-thrower with inlaid eyes. Having already undermined Riefenstahl’s purity aesthetics through the vibrant colors of his painted Olympian gods, Godard repurposes Riefenstahl’s German Olympian and presents Jeremy, an embodiment of Hollywood’s complicity in globalized capitalism, mimicking the pose and movements of Riefenstahl’s earlier icon of fascism.

In a refutation of Riefenstahl’s use of the Discobolus for Nazi propaganda in 1938, broadsheets for the Olympic Games in London in 1948 printed a photograph of the statue, reclaiming a classical icon to emphasize Allied victory in World War II.57 Excavated from the Roman emperor Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli in 1791 and, like the bust of Homer from Baiae, purchased from a dealer by British collector Charles Townley, the Townley Discobolus has been in the collection of the British Museum since 1805 (BM 1805,0703.43).58 The version acquired by Townley is distinct for its downward-facing head rather than a head tilted to look back toward the discus as other iterations have. Using the image of Townley’s Discobolus to advertise the London Games claimed victory for Allied forces and rightful inheritance of an idealized classical past for which this discus-thrower carved from Carrara marble, owned by an ancient Roman emperor, and acquired with British pounds stands in.59

This evocation of Riefenstahl’s Nazi aesthetics in Lang’s screening room scene recalls another scene in Contempt that contrasts Lang’s courage with Riefenstahl’s complicity. Paul tells Prokosch that in 1933 Joseph Goebbels asked Lang to head the German Film Industry and Lang left Germany for Hollywood that night.60 In contrast to Lang, Riefenstahl, who is not named, did Hitler’s work with her films, presenting a living discus-thrower as the modern Aryan embodiment of the classical statue. In reply to Paul’s account of Lang’s ethics, Jeremy reminds Paul that the year is not 1933 but 1963 and makes a brief salute merging into an embrace that the audience cannot fail to understand. At their initial meeting, Jeremy insists to Paul that Lang’s Germanness (he was actually Austrian) made him the right director for the Odyssey because “everybody knows that a German, Schliemann, discovered Troy,” in a dialogue that emphasizes the role of archaeological extraction in the cross-cultural consumption of classical antiquity.61 Jeremy’s discus-thrower reworks Riefenstahl’s Nazi aesthetics and their postwar reclamation, now embodied by a force of global capitalism, the money behind big budget films that both demanded and financed color technologies. Jeremy’s Discobolus emphasizes the relentless reworking of visual and linguistic meaning, wherein the same image marks seemingly opposing ideologies.

Contingencies

Cast-making contributed to the excision of color from statues, and the circulation of monochrome white plaster casts reshaped wider aesthetic expectations. Contempt’s color technologies highlight the brightly painted casts and made-up actors of Lang’s Odyssey that refuse this dominant aesthetic of classicism, while also gesturing to the cost of such polychromy—for statues and for films. Of these painted casts and their tensions with not only a picture of classical antiquity but also a version of modernism forged in relation to that image, Krauss argues that “our irritation does not arise so much from Godard’s flouting of our ignorance, as from something else: we like those statues white. We have a taste for monochrome sculpture.”62 Krauss’s universalizing “we” performs the kind of homogenization that classicism’s taste-shaping pursues, for there are, indeed, many long traditions of polychrome sculpture. Her critique also points to a problem in the study of color—that of its relentless rediscovery despite centuries of debate by the time that Godard made Contempt. In eschewing that taste, Lang’s Odyssey reintroduces color to antiquity along with all the changeableness and lack of fixity that accompanies it. The contingency of Contempt’s color, like the relationship of past and present, lies at the center of the film’s entangled ideas of ancient and modern art.

Godard filmed Contempt in Eastmancolor, a single-strip color technology introduced by Kodak in 1950.63 Eastmancolor, unlike earlier color processes, could be filmed using a standard black-and-white camera and quickly became widely used by Hollywood film companies.64 Eastmancolor was the first single-strip color film technique compatible with the wide-angle lens of Cinemascope. The opening credits highlight Contempt’s specific technologies: “It was shot in Cinemascope and printed in color by GTC in Joinville.”65 Developed in the 1920s and in regular use in the 1950s through the late 1960s, Cinemascope is an anamorphic lens technology that compresses panoramic shots so that, with the addition of a lens adapter, they can be filmed and projected like scenes shot on a regular camera. This allowed films made in Cinemascope to be shown in theaters without investing in extensive specialized equipment. With the chemist for Laboratoires GTC Paris, Godard and his team ran various color tests, but such commercial labs catered to large-scale, standardized projects and lacked the flexibility to make adjustments for the comparatively small scale of Godard’s production.66 Through scale, the technical choices of large-scale projects commanded an outsized impact on color processing, impacting smaller productions, such as Godard’s, by commandeering the processing equipment and technical settings of commercial labs.

Although shot on Eastmancolor, the credits for Lang’s Odyssey identify Technicolor as its color technology, and crew members wear jumpsuits emblazoned with the word “Technicolor” on the back, staging a contrast between the newer Eastmancolor of the film and the earlier dominant color three-strip color technology. This staging of Lang’s Odyssey as if in Technicolor performs a passage in Moravia’s novel in which the playwright laments selling out to write “a masquerade in technicolor.”67 Of Technicolor’s challenges, Contempt’s cinematographer Raoul Coutard reflected: “It’s when he is working with colour film that the cameraman is most aware of the fact that no film stock is as sensitive as the human eye. The problem comes from the fact that any number of techniques and working practices were developed for work with early colour stock, such as Technicolor, which was not very flexible.”68 The juxtaposition of the Technicolor of Lang’s Odyssey and the Eastmancolor on which Godard shot Contempt establishes a framework of technology’s inevitable, relentless obsolescence, color’s contingency, and capital’s capture of creative control.

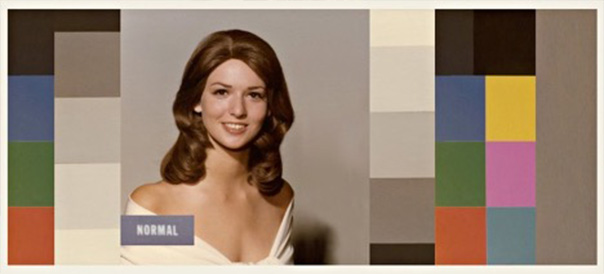

Emphasizing the contingency of color processes, a scene of Lang’s Odyssey shows a set assistant performing a color check on one of the painted statues playing the role of “the Greek statue” (fig. 14).69 Such color correction charts were an established feature of early color film technology, appearing as early as the beginning of the twentieth century.70 By the 1960s, color charts had also emerged as something of a leitmotif in the visual arts. In 1963, the year in which Godard released Contempt, David Smith painted one of the many polychrome sculptures so objected to by Greenberg, Zig VII, as a kind of color chart; Jim Dine painted The Color Chart; Alma Thomas sketched a preparatory drawing for her painting March on Washington, bringing together her engagement with the color chart and a figural depiction of the march—in which she had participated—to picture the mutual imbrication of seemingly objective color charts and constructions of race, colorism, and systemic, anti-Black racism (figs. 15–17).71 If the classical has long been associated with the figural and the color chart with abstraction, March on Washington pictures, instead, a relationship between abstraction and figuration. Similarly, paint on ancient Greek and Roman statues (and on their plaster casts) marks the entanglement of the color chart’s abstraction, color’s contingent materiality, and histories of figuration.

Also in 1963, Josef Albers published his influential book Interaction of Color, a treatise developed through his own practice and teaching that continues to shape many artists’ engagement with color.72 The book’s initial print run by Yale University Press required fundraising and collaboration to reproduce the range of color relationships that Albers sought to visualize with the standard four-color printing process paired with lithography and screen printing.73 Albers’s treatise built from a deep tradition of writing on the phenomenon of color that draws together art practice, science, and philosophy.74

As with cast-making, color has been theorized and debated or contested since antiquity. The fourth century BCE ancient Greek artist Euphranor’s no-longer-extant work Peri khromaton (On Colors) engaged with and shaped art practice and philosophy.75 The physicist Isaac Newton’s prism experiments from the 1690s (published in Opticks in 1704) established the modern ROYGBIV spectrum. The philosopher Johann Goethe countered Newton’s spectrum with a materialist argument in Zur Farbenlehre (Theory of Colors) of 1810 (translated into English in 1840). Michel Eugène Chevreul’s book of color contrasts drawn from experience in the textile dying industry, De la loi du contraste simultané des couleurs (Law of Simultaneous Contrasts of Colors) of 1839, deeply influenced Impressionism.76 In the production of his practical color guide Modern Chromatics with Applications to Art and Industry (1879), physicist Ogden Rood noted his long engagement with artists and his own experiments with drawing and painting.77 W. E. B. Du Bois exhibited his brightly colored handmade data visualizations of the lived experiences of African Americans in the state of Georgia since the end of the US Civil War exhibited at the Paris World’s Fair of 1900.78 The chemist Wilhelm Ostwald’s color experiments, published in Die Farbenfibel (The Color Primer, 1916), contributed to the development of photography’s grayscale.79 Alexander Munsell’s Munsell Book of Color (1929) sought to codify the range of visible colors to allow for comparative study of, for example, layers of soil and remains in use by environmental scientists and archaeologists today.80 As contemporary artist Tomashi Jackson has explored, Albers’s studies resonated with a similar analysis of the relativity of color a decade earlier by Justice Thurgood Marshall in his US Supreme Court opinions on desegregation.81 Interaction of Color, the color treatises that preceded it, and the many artistic engagements with the color chart—from Zig VII to the color check in Lang’s Odyssey—picture relationships between colors not as given and fixed but as relentlessly changing and contingent. Recognizing color’s liminal state refuses the sorts of categorical arguments about race and gender into the service of which ideas about color have so often been pressed.

The color correction card held up against the face of a painted “Greek statue” in Lang’s Odyssey draws from the imagery of Kodak’s own Shirley cards, which were used to set the standard by which Kodak calibrated its color printing process for still photographs (fig. 18).82 Keyed to the skin of a white woman, the first of whom was ostensibly an employee of the company named Shirley, the cards modeled a white, femme body against which to measure a photograph’s colors, embedding racism in the technical production of color film. Building from this history in the color check scene, Godard substitutes a polychrome Greek statue for the Shirley, marking the enduring slippage between unpainted marble and whiteness and painting over this fiction.

In contrast to the polychrome statues playing the gods, the human actors in Lang’s Odyssey wear thick, opaque makeup, which showcases the technical relationship between such additive colors and color film technology (see figs. 2 and3). While the eye sockets of the gods were painted, the human actors wear bands of makeup across their eyes and are shot against backgrounds painted with contrasting colors. The thickness and opacity of their makeup highlights the important technical role of makeup in color film production. A conversation between Paul and Lang watching the daily takes gestures to this significance. “I really like Cinemascope,” Paul offers, trying to engage Lang. As the character directing Lang’s Odyssey, Lang replies quoting himself, “It’s not made for people. It’s only good for snakes and funerals.”83 This derision of Cinemascope engages a standing problem of how cinematographic color picked up flesh tones.

Color labs developing color film used the actors’ faces as a “fixed point” on which to base the overall color scheme, and this required actors to wear specific makeup to standardize their skin tones for the labs.84 Early Technicolor test scenes, for example, include a sequence assessing different greasepaint tones on the skin of a white man’s face.85 Coutard describes the intersecting problems of makeup, film technology, and capital: “All make-up men, however, have been trained in the American techniques which date back to the early days of Technicolor. They make up the actors very red, a practice which apparently was necessary for Technicolor.”86 By 1963, when Contempt came out, Max Factor’s Pan-Cake Make-Up dominated the Hollywood makeup industry, having defeated Elizabeth Arden in “the Hollywood Powder Puff Wars.”87 Max Factor realized this commercial dominance, Kristy Sinclair Dootsin argues, by centering whiteness in their production of makeup compatible with Technicolor’s three-strip color process.88 The standardization of film makeup, like the standardization of color film technologies and lab processing, constructed whiteness as a default standard. This encouraged directors to cast white actors for whom film makeup was keyed, and perpetuated that default standard off-screen through marketing tie-ins.89 For films connected to the classical past, such casting decisions upheld a false picture of the racialized whiteness of Mediterranean antiquity and, in dialogue with the roles performed by ancient art in these films, recursively shaped ideas about color and classical art. Godard cast made-up actors and painted casts to perform Lang’s polychrome Odyssey, staging a montage of the technical and social contingencies of color and classicism.

Conclusion

In Contempt’s mid-century perspective on color, cinematic technologies, the twentieth century’s redeployment of antiquity, and ancient art itself all coalesce. Monochrome white surfaces like those cast by archaeologists at Pompeii and celebrated by Riefenstahl’s Olympia haunt the art historical and cinematographic traditions.90 Godard’s bright pigments and filters, in contrast, spotlight and animate that spectral lineage.

By the end of the film, both Camille and Jeremy are dead, Paul plans to return home to Rome, and Lang forges ahead with his Odyssey. The film crew in their Technicolor jumpsuits zoom in on Odysseus, who faces the Tyrrhenian Sea.91 The final frames of Contempt continue to bring together painted statues, made-up people, color filters, and wide-angle land- and seascapes.

Godard, playing Lang’s assistant, holds the clapperboard labeled “Odysseus.” The camera draws closer and closer to the word “Technicolor” on the crew’s jumpsuits before panning past their bodies, over Odysseus’s, until only the body of blue water fills the frame (fig. 19).92 Godard calls out “silence” and someone translates “silencio.” Color in Contempt produces a contingent and recursive polychrome world, not as we see it but perhaps one more in harmony with our desires.

Jennifer M. S. Stager

Jennifer M. S. Stager, assistant professor in the department of art history at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, is a writer and art historian focusing on the art and architecture of the ancient Mediterranean and its afterlives. Her areas of research include theories of color, materiality, feminisms, multilingualism, ancient Greek medicine, and classical receptions. Stager is the author of Seeing Color in Classical Art (2022) and, with Leila Easa, Public Feminism in Times of Crisis: From Sappho’s Fragments to Viral Hashtags (2022).

Thank you to the anonymous peer reviewers and to the editorial and production teams at West 86th, especially Katherine Atkins, Nick Geller, and Caspar Meyer. Thank you to Lauren Grabtree, M. Brian Cole, Lael Ensor-Bennett, Marian Feldman, Sarah Hamill, Aaron Hyman, Donald Juedes, Lisa Regan, and Mackenzie Zalin for feedback and infrastructural support. Audiences of Cornell’s “Siren Echoes: Sound, Image, and the Media of Antiquity” conference (2019) and New York University’s Daniel H. Silberberg Lecture (2023) greatly enriched aspects of this paper.

- 1 Rosalind Krauss, “Changing the Work of David Smith,” Art in America 62, no. 5 (1974): 30.

- 2 Krauss, “Changing the Work of David Smith,” 30–31; Sarah Hamill, “Polychrome in the Sixties: David Smith and Anthony Caro,” in Anglo-American Exchange in Postwar Sculpture, 1945–1975, ed. Rebecca Peabody (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011), 93nn9–10; and Hamill, David Smith in Two Dimensions: Photography and the Matter of Sculpture (University of California Press, 2015), 127–28.

- 3 For a selection of exhibitions and publications on ancient polychromy, see Jennifer M. S. Stager, Seeing Color in Classical Art: Theory, Practice, and Reception, from Antiquity to the Present (Cambridge University Press, 2022), 2–3n6.

- 4 Krauss, “Changing the Work of David Smith,” 30–31. Contempt’s polychrome statues intervene in a monochrome modernism formed in relation to the fiction of a monochrome antiquity—what David Smith called in the 1940s “the dead dark [of bronzes] and marble, dead white”; see Hamill, “Polychrome in the Sixties,” 91. Smith, however, knew this monochrome for fiction having traveled to Greece in the mid-1930s and, according to his letters to friends, sampled pigments from Greek statues; see Sarah Hamill and David Smith, David Smith: Works, Writings and Interviews (Ediciones Polígrafa, 2011). On the importance of Godard’s painted statues for the archaeologist Jean Marcadé’s ideas about ancient polychromy, see Philippe Jockey, “Les couleurs et les ors retrouvés de la sculpture,” Revue Archaeologique 58, no. 2 (2014): 368–70.

- 5 Emilie Bickerton, A Short History of Cahiers du cinéma (Verso, 2009), ix, citing Godard in Cahiers du cinéma (1959).

- 6 Richard T. Neer has explored the role of painting in Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinéma, including Godard’s engagement with Seurat, Turner, and Laughton: “For Godard, as for Malraux, Bazin, and many others, cinema stands to painting as child to mother”; see Neer, “Godard Counts,” Critical Inquiry 34, no. 1 (2007): 154. On painting, tableaux vivants, and Godard’s Passion (1982), see Steven Jacob, Framing Pictures: Film and the Visual Arts (Edinburgh University Press, 2011), 107–17.

- 7 Bickerton, A Short History of Cahiers du cinéma, ix, citing Godard in Cahiers du cinéma (1959).

- 8 In his essay on Le mépris in Cahiers du cinéma, Godard describes Moravia’s novel as a “un vulgaire et joli roman de gare”; Jean-Luc Godard, “Le mépris,” Cahiers du cinéma 147 (1963): 31. Of the split setting, Godard describes Rome as “le monde modern, l’Occident” and Capri as “le monde antique, la nature avant la civilisation et ses névroses”; see Godard, “Le mépris,” 31. The double issue of Cahiers du cinéma (vols. 21–24) spanning December 1962 to January 1964 included Godard among the filmmakers commenting on the state of American cinema (12–23), and Lang is among those American filmmakers profiled.

- 9 David Smith also photographed painted statues within a landscape. While Budnik’s color photographs of Smith’s sculpture serves as evidence for Krauss’s claim that Greenberg contributed to the excision of their painted colors, Sarah Hamill has also demonstrated the importance of Smith’s carefully staged color photographs in his polychrome practice; see Hamill, “Polychrome in the Sixties,” 98. Notably, Krauss published a second essay, also titled “Changing the Work of David Smith,” Art Journal 43, no. 1 (1983): 89–95, that tackled precisely this relationship.

- 10 On the transmission history of Homer, see Joseph Farrell, “Roman Homer,” in The Cambridge Companion to Homer, ed. Robert Fowler (Cambridge University Press, 2004), 254–71; Glenn W. Most and Alice Schreyer, eds., Homer in Print: A Catalogue of the Bibliotheca Homerica Langiana at the University of Chicago Library (University of Chicago Library, 2013); Barbara Grasiozi, “On Seeing the Poet: Arabic, Italian, and Byzantine Portraits of Homer,” Scandinavian Journal of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, no. 1 (2015): 25–48; Edin Muftić, “Homer: An Arabic Portrait,” Pro tempore 13 (2018): 21–41; and James I. Porter, Homer: The Very Idea (University of Chicago Press, 2021), especially the timeline on xi–xiv, with bibliography. On the Odyssey and cinema, see Edith Hall, The Return of Ulysses: A Cultural History of Homer’s Odyssey (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 27–29.

- 11 Godard, “Le mépris,” 31. Here Godard drops a phrase that was also the title of the influential literary and theoretical journal Tel quel, in which Godard and others regularly published; see Patrick Ffrench, The Time of Theory: A History of Tel quel (1960–1983) (Oxford University Press, 1996). Notably, Moravia eschews epic’s third-person narrator in favor of the first person; see Hall, The Return of Ulysses, 28.

- 12 Jean-Luc Godard, Le mépris (Contempt), 18:54–19:00.

- 13 In the film’s original Italian release, its producer Carlo Ponti dubbed the entire film into Italian, eliding Godard’s attention to translation; see Dave Kehr, “Gods in the Details: Godard’s Contempt,” Film Comment 33, no. 5 (1997): 20.

- 14 Godard, Contempt, 29:01–29:51. See also Jockey, “Les couleurs,” 369; and Jean Marcadé, Roma amor: Essays on Erotic Elements in Etruscan and Roman Art (Nagel, 1961).

- 15 Godard, Contempt, 33:07–33:22.

- 16 On geographical disputes over the location of the Sirens in antiquity, see Strabo, Geographica (Geography), 1.6.1.

- 17 Victor Bérard, Dans le sillage d’Ulysse: Album odysséen (Armand Colin, 1933).

- 18 Ernle Bradford, Ulysses Found (Hodder and Stoughton, 1964), 133–46. In the twenty-first century, Friedrich Kittler and his partners also located Odysseus’s encounter with the Sirens off of Capri, where he conducted sound experiments with opera singers Louise Schumacher and Katie Mullins as Sirens; see Kittler, “In the Wake of the Odyssey,” Cultural Politics 8, no. 3 (2012): 413–27, mentioning Godard; and Tanvi Solanki, “The Media Archaeological Ear and the Difference That Goes Unheard,” in Coming to Know, ed. Nida Ghouse and Brooke Holmes (Archive Books, 2020), 22–39.

- 19 Godard’s staging of the Sirens also echoes a sequence from Jean Renoir’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Picnic on the Grass, 1959), which he also cites in other scenes of Lang’s Odyssey.

- 20 On the renovations of the archaeological park at Sperlonga, which were ongoing during the filming of Contempt, see Carmen Carbone Stella Richter, Sperlonga, 1948–1968: L’architettura della riconstruzione (Prospettive Edizioni, 2008). On the sculpture group, see Andrew F. Stewart, “To Entertain an Emperor: Sperlonga, Laokoon and Tiberius at the Dinner-Table,” Journal of Roman Studies 67 (1977): 76–90; Nikolaus Himmelmann, Sperlonga: Die homerischen Gruppen und ihre Bildquellen (Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 1995); and Matthias Bruno, Donato Attanasio, and Walter Prochaska, “The Docimium Marble Statues of the Grotto of Tiberius at Sperlonga,” American Journal of Archaeology 119, no. 3 (2015): 375–94. On depictions of Homeric scenes in Roman painting and in the sculptures from Sperlonga, see Farrell, “Roman Homer,” 259–62.

- 21 On color language in Homer, see Stager, Seeing Color in Classical Art, 38, 51–52.

- 22 W. E. Gladstone, Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age (Oxford University Press, 1858).

- 23 Gladstone, Studies on Homer and the Homeric Age, 17.

- 24 Franz Kugler, Über die Polychromie der griechischen Architektur und Sculptur und ihre Grenzen (Gropius, 1835), 12–24; J.-I. Hittorf, “On the Polychromy of Greek Architecture,” Museum of Classical Antiquities: A Quarterly Journal of Ancient Art 1, no. 3 (1851): 20–34; Gottfried Semper, “On the Study of Polychromy, and Its Revival,” Museum of Classical Antiquities: A Quarterly Journal of Ancient Art 1, no. 3 (1851): 228–46; Owen Jones, Great Exhibition (London, 1851); and John Gibson, Tinted Venus (1852–56). On the contemporaneity of Gladstone’s work and these thinkers, see John Gage, Color and Meaning: Art, Science, and Symbolism (University of California Press, 1999), 12.

- 25 Godard’s colors thus counter approaches to the reconstruction of color on ancient Greek and Roman statues that aimed to make the statues likelife.

- 26 Cast collections circulated a canon of Greek and Roman sculpture with which artists and scholars alike trained from at least the fifteenth century, but by the mid-twentieth century many institutions had rid themselves of their cast collections, considering them to be inauthentic copies; see Rune Frederiksen and Eckart Marchand, eds., Plaster Casts: Making, Collecting and Displaying from Classical Antiquity to the Present (Walter de Gruyter, 2010).

- 27 For a photograph of the statue, see https://media.un.org/photo/en/asset/oun7/oun7770016. The ancient bronze statue originally had eyebrows made of silver, lips of copper, and (now missing) inlaid eyes; see Christos Karouzos, “The Find from the Sea off Artemision,” Journal of Hellenic Studies 49, part 2 (1929): 141–44. The United Nations cast (UNNY129G) is one of only two distributed by the Greek government; the other was given to the University of Melbourne in commemoration of the 1956 Olympic Games; see Andrew Jamieson and Hannah Gwyther, “Casts and Copies: Ancient and Classical Reproductions,” University of Melbourne Collections 8 (2011): 50.

- 28 The Baiae cast workshop also included a fragment of the Athena Velletri type; see Christa Landwehr, “The Baiae Casts and the Uniqueness of Roman Copies,” in Frederiksen and Marchand, Plaster Casts, 35.

- 29 On ancient reproductions of the Athena Parthenos, see Milette Gaifman, “Statue, Cult and Reproduction,” Art History 29, no. 2 (2006): 258–79.

- 30 On the Aphrodite of Knidos, see Andrew Stewart, Greek Sculpture: An Exploration (Yale University Press, 1990), 177–78, T 95–100.

- 31 On the many reproductions of the Aphrodite of Knidos from antiquity, see Kristen Seaman, “Retrieving the Original Aphrodite of Knidos,” Rendiconti: Classe di scienze morali, storiche e filologiche, ser. 9., vol. 15, no. 3 (2004): 531–94. Among these reproductions of the Knidian Aphrodite is the Aphrodite of Baiae, a marble statue produced in the second century CE, discovered in 1809 by a British antiquarian, restored by the artist Antonio Canova, and given to the National Archaeological Museum in Greece in 1924 (NAM 3524). Working with plaster casts shaped Canova’s own sculptural practice in marble; see Johannes Myssok, “Modern Sculpture in the Making: Antonio Canova and Plaster Casts,” in Frederiksen and Marchand, Plaster Casts, 269–88.

- 32 On the traces of gilding, red ochre, and Egyptian blue identified during the 2012 restoration, see Antonio Natali, Allesandro Nova, and Massimiliano Rossi, eds., La tribuna del principe: Storia, contesto, restauro; Colloquio internazionale, Firenze, Palazzo Grifoni, 29 novembre–1 dicembre 2012 (Giunti, 2014).

- 33 The brown color of the painted pubic hair of this cast might gesture toward Courbet’s painting L’origine du monde (The Origin of the World, 1866).

- 34 For example, in 1903, Diego Rivera drew a plaster cast of the Venus de Milo (08-639498) in the collection of the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (08-646392) as if the cast were prone; see Elizabeth Fuentes Rojas, “Art and Pedagogy in the Plaster Cast Collection of the Academia de San Carlos in Mexico City,” in Frederiksen and Marchand, Plaster Casts, 241, fig. 11.8, with discussion of the cast collection in Mexico City; and Camille Mathieu, “Origin Points, Archaeology, and the Search for Authenticity,” in Picasso and Rivera: Conversations Across Time, ed. Michael Govan and Diana Magaloni (Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Prestel, 2016), 72–95. In the music video for the Carters’ song “Ape$shit” (2018), shot in the Louvre, a dancer emulates the statue’s missing arms.

- 35 On Jean Renoir filming in settings in which Impressionists also painted, see David Hanley, “In His Father’s Steps: Jean Renoir’s Evolving Relationship with Impressionism in Partie de campagne and Le déjeuner sur l’herbe,” Offscreen 26, nos. 1–2 (2022), https://offscreen.com/view/In_His_Fathers_Steps_Jean_Renoirs_Evolving_Relationship_with_Impressionism_in_Partie_de_campagne_and_Le_dejeuner_sur_lherbe.

- 36 Laura Anne Kalba, Color in the Age of Impressionism: Commerce, Technology, and Art (Penn State University Press, 2017), 81, 116–17. Godard cites Manet’s Le déjeuner sur l’herbe more directly in Passion (1982); see Jacobs, Framing Pictures, 115.

- 37 Kalba, Color in the Age of Impressionism, 81.

- 38 On the intersection of women’s beauty and film’s beauty in Godard, see Laura Mulvey, “Le mépris (Jean-Luc Godard 1963) and Its Story of Cinema: A ‘Fabric of Quotations,’” in From La Strada to the Hours: Suffering and Sovereign Women in the Movies, ed. Vivian Pramataroff-Hamburger and Andreas Hamburger (Springer, 2024), 40.

- 39 Kaja Silverman and Harun Farocki, Speaking about Godard (New York University Press, 1998), 37–38.

- 40 This marble bust from Baiae is now in the British Museum, having come through the collection of Charles Townley: BM 1805,0703.85; others include: Paris, Louvre MR 530; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 04.13; and Rome, Palazzo Massimo 126371. Prints, engravings, black-and-white photographs, and plaster casts circulated monochrome or tonal images of the bust widely. Rembrandt painted such a bust, possibly working from a version in his personal collection, in Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer (1653), commissioned by the Italian collector Antonio Ruffo and painted in Amsterdam during a time of financial insecurity for the artist before traveling to Sicily, London, and eventually New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art 61.198); see Nicola Suthor, Rembrandt’s Roughness (Princeton University Press, 2018), 131–33.

- 41 Gisela M. A. Richter, “An Aristogeiton from Baiae,” American Journal of Archaeology 74, no. 3 (1970): 296–97; on ancient cast production, see Rune Frederiksen, “Plaster Casts in Antiquity” in Frederiksen and Marchand, Plaster Casts, 13.

- 42 Christa Landwehr, Die antiken Gipsabgüsse aus Baiae: Griechische Bronzestatuen in Abgüssen römischer Zeit (Mann, 1985); see also Landwehr, “The Baiae Casts,” 37, emphasizing the labor that producing such casts in antiquity required.

- 43 Richter, “An Aristogeiton from Baiae,” 74. On inlaid eyes in ancient bronze statues, see Carol C. Mattusch, “In Search of the Greek Bronze Original,” in “The Ancient Art of Emulation: Studies in Artistic Originality and Tradition from the Present to Classical Antiquity,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, supplementary volume 1 (2002): 99–115.

- 44 On artistic debates in the fifteenth–seventeenth French and Italian academies, see Jacqueline Lichtenstein, The Blind Spot: An Essay on the Relations between Painting and Sculpture in the Modern Age, trans. Chris Miller (Getty Research Institute, 2008).

- 45 Although described here in a comedy, Hermes’s comment suggests that sign languages were a regular part of communication in the ancient Mediterranean.

- 46 LSJ, “pissoō.” The verb for covering a statue with pitch (pissoō) Lucian uses elsewhere (Rhetorum praeceptor) to describe not mold-making but depilation, an ambiguity on which he certainly plays in this passage—one might be coated in pitch to make a cast or to be depilated. Godard’s gold-and-brown painted pubic triangles refuse the depilated norms that viewers associated with unpainted classical nudes, norms that Lucian indicates were already in flux in antiquity. The corslet (thorax), much like a fitted breastplate for a warrior, presses against the statue’s body to enable sculptors to take a mimetic impression, a haptic procedure emphasized by the participle of ek-tupō (to model, to work in relief, to take an impression) and the noun sphragis (seal, sealing), words regularly used for the serial reproduction of impressions. In addition to meaning a material mark or impression signaling ownership or authority, a seal (sphragis) also operates as a rhetorical term for an author’s stylistic mark, a doubleness that, like the gesture toward depilation, might here constitute a kind of sphragis for Lucian; see Deborah H. Roberts, “sphragis,” in The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th ed. (Oxford University Press, 2012). On ancient Graeco-Roman impressions, see Verity Platt, “Making an Impression: Replication and the Ontology of the Graeco-Roman Seal Stone,” Art History 29, no. 2 (2006): 233–57.

- 47 Marcia Pointon, “Casts, Imprints, and the Deathliness of Things: Artifacts at the Edge,” Art Bulletin 96, no. 2 (2014): 170–95; Patrick R. Crowley, “Roman Death Masks and the Metaphorics of the Negative,” Grey Room 64 (2016): 64–103.

- 48 On the quotations in this scene and the cinematographic relationship between the statues in Lang’s Odyssey and Rossellini’s Journey to Italy, see Laura Mulvey, “Le mépris,” 35–37.

- 49 Mulvey, “Le mépris,” 41–42.

- 50 Roberto Rossellini, Viaggio in Italia (Journey to Italy, 1954), 1:12:17–1:1219.

- 51 Steven Jacobs analyzes the connection between death and museums in Rossellini’s Journey to Italy and Hitchcock’s Vertigo, briefly mentioning the scene in Bande à part (Band of Outsiders, 1964), in which the three main characters race through the Louvre to beat the time logged by an American tourist to do the museum; see Jacobs, Framing Pictures, 65–87. To this sequence, I would add Ryan Coogler’s museum scene in Black Panther (2018) works in this tradition of cinematographic commentary on the nature of the museum.

- 52 Rossellini, Journey to Italy, 29:01–29:06. On the archaizing art and literature of the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum, see Kenneth D. S. Lapatin, ed., Buried by Vesuvius: The Villa Dei Papiri at Herculaneum (J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019).

- 53 The image of a discus-thrower is also painted on the wall of the Villa Arianna in Stabiae, near Pompeii.

- 54 Goddard, Contempt, 19:17–19:20.

- 55 Michel Delahaye, “Leni et le loup: Entretien avec Leni Riefenstahl,” Cahiers du cinéma 170 (1965): 43–51, presented an interview with Riefenstahl in which she pled innocence while also justifying her purity aesthetics as a “love of beauty” (44). For documentation of Olympia’s Nazi financing, see Hans Barkhausen, “Footnote to the History of Riefenstahl’s ‘Olympia,’” Film Quarterly 28, no. 1 (1974): 8–12. On Riefenstahl’s mobilization of ancient Greek nude male statues to stage Aryan masculinity, see Daniel Wildmann, “Desired Bodies: Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia, Aryan Masculinity, and the Classical Body,” in Brill’s Companion to the Classics, Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, ed. Helen Roche and Kyriakos N. Demetriou (Brill, 2017), 60–81. Susan Sontag’s celebrated essay on Riefenstahl’s aesthetics rejects the whitewashing of her role in the Third Reich and claims of denazification; see Sontag, “Fascinating Fascism,” New York Review of Books 22, no. 1 (1974): 5. Notably, Sontag published this in the same year Krauss published her critique of Greenberg.

- 56 On the discovery, naming, and competing claims to the Lancellotti Discobolus, see Günter Grimm, “Myrons geraubter Diskobol oder: Wer hat wen bestohlen?,” Antike Welt 34, no. 1 (2003): 59–68. On Hilter’s purchase and Mussolini’s role in allowing the statue’s export, see Irene Bald Romano, “Collecting Classical Antiquities Among the Nazi Elite,” RIHA Journal 0283 (September 15, 2023), https://doi.org/10.11588/riha.2022.2.92736, including a black-and-white photograph (fig. 5) of Hitler standing in front of the statue in Munich in 1938.

- 57 British Museum 2007,5006.1; see also Ian Jenkins, “Patriotic Hellenism: A Poster for the 1948 London Olympics,” Print Quarterly 28, no. 4 (2011): 451–55.

- 58 In addition to Homer’s bust and Hadrian’s Discobolus, Charles Townley also collected a copy of the Iliad written down on parchment around 1059 CE and filled with centuries of marginalia into which he inserted both an engraving of his own portrait and an engraving of the bust of Homer on the recto, British Library, Burney MS 86 (see fig. 4).

- 59 The British Museum also has a Jesmonite cast with wax finish (2012,5027.1).

- 60 Goddard, Contempt, 9:56–10:20.

- 61 Goddard, Contempt, 8:38–8:49.

- 62 Krauss, “Changing the Work of David Smith,” 30–31. Krauss’s “we” does a lot of work, encompassing the overlapping audiences of Greenberg, whose embrace of medium specificity paint on sculpture certainly violates, Godard, and the art world audience following the fallout of Greenberg’s posthumous interventions, although it also excludes a “we” who might embrace such polychromy, the very “we” sidelined by Greenberg’s art world operations.

- 63 On Kodak’s three-color single strip, see G. J. Craig, “Eastman Colour Films for Professional Motion Picture Work,” British Kinematography 22, no. 5 (1953): 146–58; and Dudley Andrew, “The Post-War Struggle for Colour,” in Color: The Film Reader, ed. Angela Dalle Vacche and Brian Price (Routledge, 2006), 47.

- 64 Frederick Foster, “Eastman Negative-Positive Color Films for Motion Pictures,” American Cinematographer 34, no. 7 (1953): 322–33, 348.

- 65 Goddard, Contempt, 2:21–2:25. On the history of Laboratoires G.T.C. Paris, see François Ede, GTC: Histoire d’un laboratoire cinématographique (Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, 2016).

- 66 Raoul Coutard, “Light of Day: Raoul Coutard on Shooting for Jean-Luc Godard,” Sight and Sound (September 9, 2016), https://www2.bfi.org.uk/news-opinion/sight-sound-magazine/features/raoul-coutard-shooting-film-jean-luc-godard; originally published in Sight and Sound 35, no. 1 (1965–66): 9–11, and translated from the French, “La forme du jour,” Le nouvel observateur (September 22, 1965): 36.

- 67 Moravia writes “una maschetrata Technicolor”; see Alberto Moravia, Il Disprezzo (Valentino Bompiani, 1954), 212, cited in Anne Carson, “Contempts,” Arion 16, no. 3 (2009): 6.

- 68 Coutard, “Light of Day.”

- 69 Godard, Contempt, 13:54.

- 70 On early color film technologies, see the exhibition Before Technicolor: Early Color on Film, Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 20, 2023–July 21, 2024. Selections include a color chart used in “A Make-Up Test for Luis Alberni and a Make-Up for Alberni and Frank Morgan for The Dancing Pirate, 1936,” in Technicolor Tests (1933–36, compiled 1954), 4:50–5:57.

- 71 On the color chart in the mid-twentieth century and Jim Dine, see Ann Temkin and Briony Fer, Color Chart: Reinventing Color, 1950 to Today, exh. cat. (Museum of Modern Art, 2008), 78–79, no. 20, although the exhibition does not include work by either David Smith or Alma Thomas. For Dine’s sketches of classical casts in the Munich Glyptothek, see Jim Dine, Ruth Fine, and Stephen Fleischman, Drawing from the Munich Glyptothek (Madison Art Center; Hudson Hills Press, 1993). On Zig VII (Museum of Modern Art, New York, 119.1984) and Smith’s polychromy, see Hamill, David Smith in Two Dimensions, 134–41. On Alma Thomas and her sketch for March on Washington (Columbus Museum, Georgia, G.1994.20.28), see Seth Feman and Jonathan Frederick Walz, Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful (Columbus Museum; Yale University Press, 2021), no. 105; on Thomas teaching with plaster casts, see 111, fig. 2, and 119, fig. 3. For a poetic engagement with Thomas’s colorwork, see Eve Shockley, “alma’s arkestral vision (or, farther out),” in suddenly we (Wesleyan University Press, 2023), 1–10.

- 72 Josef Albers, Interaction of Color (Yale University Press, 1963).

- 73 Brenda Danilowitz, “A Short History of Josef Albers’s Interaction of Color,” in Intersecting Colors: Josef Albers and His Contemporaries, ed. Vanja Malloy (Amherst College Press, 2015), 20.

- 74 For an expansive analysis grappling with the phenomenon of color as it intersects with cultural history, science, and art production, see John Gage, Color and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction (Little, Brown, 1993) and Gage, Color and Meaning, both of which explore the nexus of color-writing within which Albers and others produced their work.

- 75 On Euphranor’s text, see Gage, Colour and Culture, 14; and J. J. Pollitt, “Peri chromaton,” in Color in Ancient Greece: The Role of Color in Ancient Greek Art and Architecture (700–31 B.C.), ed. M. A. Tiverios and D. S. Tsifakis (Aristotle University, 2002), 1–8.

- 76 Kalba, Color in the Age of Impressionism, 72–76.

- 77 Ogden N. Rood, Modern Chromatics with Applications to Art and Industry (Appleton, 1879), vi.

- 78 Du Bois’s data visualizations were first published in book form in 2018: Whitney Battle-Baptiste and Britt Rusert, W. E. B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America (Princeton Architectural Press, 2018); see also Annette Gordon-Reed, “The Color-Line,” New York Review of Books 68, no. 13 (2021), https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2021/08/19/du-bois-color-line-paris-exposition/. On the model of “datafiction” proposed by Du Bois, see David Bering-Porter, “Data as Symbolic Form: Datafication and the Imaginary Media of W. E. B. Du Bois,” Critical Inquiry 48, no. 2 (2022): 262–85.

- 79 Wilhelm Ostwald, The Color Primer (Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1969). See also Gage, Color and Meaning, 257–60.

- 80 A. E. O. Munsell, Munsell Book of Color: Defining, Explaining, and Illustrating the Fundamental Characteristics of Color (Munsell Color Company, 1929). See also Gage, Color and Meaning, 17, 65, situating Munsell within a range of color thinkers. Artist Ellsworth Kelly owned a copy of the Munsell Book of Color, ca. 1942, to which he added his own squares of color; see Temkin and Fer, Color Chart, 46, fig. 1.

- 81 Risa Puleo, “The Linguistic Overlap of Color Theory and Racism,” Hyperallergic, December 14, 2016; and Jennifer Roberts, “Introduction,” in Brown II, ed. Tomashi Jackson (Radcliffe Institute, 2021), 9; and Martha Buskirk, “Tomashi Jackson: Across the Universe,” Burlington Contemporary, November 27, 2024, https://contemporary.burlington.org.uk/reviews/reviews/tomashi-jackson-across-the-universe. In Brown II, Jackson describes her mixed media converging in the space of video and emerging as printed photograph; see Jackson, “Opening Discussion for Brown II,” September 20, 2021, https://www.radcliffe.harvard.edu/event/2021-opening-discussion-for-brown-ii-virtual.

- 82 On the history of the Shirley cards and their continued impact on digital technologies, see Lorna Roth, “Looking at Shirley, the Ultimate Norm: Colour Balance, Image Technologies, and Cognitive Equity,” Canadian Journal of Communications 34, no. 1 (2009): 111–36; and Roth, “Making Skin Visible Through Liberatory Design,” in Captivating Technology: Race, Carceral Technoscience, and Liberatory Imagination in Everyday Life, ed. Ruha Benjamin (Duke University Press, 2019), 275–307.

- 83 Goddard, Contempt, 17:57–18:05. See also Kehr, “Gods in the Details,” 22.

- 84 Coutard, “Light of Day.”

- 85 “A Make-Up Test for Douglas Walton, Followed by a Test of Him Without Make-Up, Showing the Use of Paints to Tone Down the Natural Color of His Face,” in Technicolor Tests, 6:20–7:42.

- 86 Coutard, “Light of Day.”

- 87 On the battle of the makeup brands, see Kirsty Sinclair Dootson, “‘The Hollywood Powder Puff War’: Technicolor Cosmetics in the 1930s,” Film History 28, no. 1 (2016): 108.

- 88 Dootson, “‘The Hollywood Powder Puff War,’” 108.

- 89 Dootson, “‘The Hollywood Powder Puff War,’” 109.

- 90 On quotation as haunting, see Mulvey, “Le mépris,” 42.

- 91 In its refusal of a crisp resolution, Contempt is neatly Homeric. Ancient scholars argued that the Odyssey should have ended when Penelope and Odysseus end up back in bed together in Book 23; see Emily Wilson, “Introduction,” in Homer, The Odyssey, trans. Wilson (W. W. Norton, 2017), 72.

- 92 On the sea in the Odyssey, see Alex Purves, “Homer and the Simile at Sea,” Classical Antiquity 43, no. 1 (2024): 97–123.