Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA

This article appears in West 86th Vol. 32 No. 1 / Spring–Summer 2025

By analyzing artist Rose Salane’s photographs of confessions written by tourists who pilfered items from the Pompeii archaeological site, this article explores the power of the material world to act on the human conscience despite the deadening effects of capitalism.

It is common, in Western anthropology as in Western culture more broadly, to conceive of magic as a force that people exert upon the material world. But it might be equally important to view it as a force that the material world exerts upon us. Insisting firmly on the vitality of matter, a series of photographs by the New York–based artist Rose Salane (b. 1992) vividly opens perspectives on magic beyond a strictly unidirectional human emanation.

Salane’s practice excavates uncanny collections of objects that accumulate because of almost random but astonishingly recurrent vicissitudes. For the 2022 Whitney Biennial, she made an installation from 64,000 meticulously inventoried “slugs”—metal washers, foreign coins, casino chips, and religious medallions—that fare-dodgers used in place of tokens to board New York City buses. Salane calls obscure repositories for collections like this one—which she purchased at a Metropolitan Transportation Authority auction in 2020—“basins of attraction,” the mathematical term for the points toward which a dynamical system tends to converge.

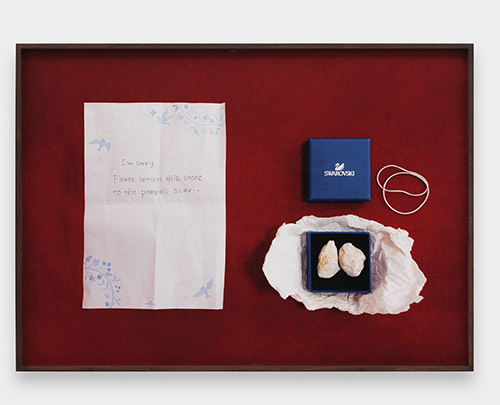

In 2022, as artist in residence at the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, she discovered another basin of attraction. Each year, some of the millions of tourists who visit the ancient Roman city destroyed by Mount Vesuvius take home illicit souvenirs: pebbles, nails, fragments of marble, shards of pottery, or even just handfuls of dirt. And each year, often long after the fact, some mail these items back, along with letters in which they confess, apologize, and ask that the pilfered objects be returned to their rightful places (fig. 1).

Like “wishcycling,” this is easier said than done in a 440,000-square-meter archaeological site. Thus, these returns accumulate in a storeroom, a pent-up battery of magical materiality waiting for Salane to tap.

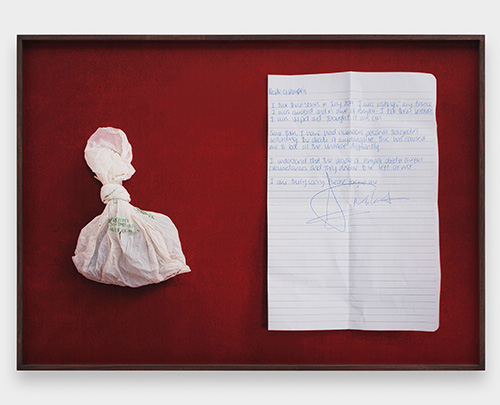

I first encountered the large-scale photographs she made of these returned objects and their accompanying confessions as part of MASS MoCA’s Like Magic exhibition (2023–25), curated by Alexandra Foradas. In one image (fig. 2), next to a dirty, knotted baggie of pebbles, a note reads:

People of Pompeii,

I took these stones in July 2019. I was visiting [with?] my fiancé. I was amazed and in awe of Pompeii. I took them because I was stupid and thought it was cool.

Since then, I have had numerous personal tragedies including the death of my daughter. This has caused me to look at the universe differently.

I understand the people of Pompeii died in awful circumstances and they deserve to be left at rest.

I am truly sorry. Please forgive me.

Even in an exhibit packed with potent magical signifiers, Salane’s images made me feel the presence of magic with particular intensity. This is due, in no small part, to the way that they intimate a record of shifting power between people and material objects. As a viewer, I couldn’t help but feel the growing pangs of conscience—and even dawning terror—as a handful of coveted pebbles slowly suggests it may be the source of a dire malediction.

This transformation also entails a shift in the status of the stolen objects. What begins, for the thieves, as a trivial souvenir—a commodity fetish that mnemonically signifies a tourist attraction—discloses alternative indexical valences as a scientifically serious artifact of a bygone civilization and a magico-religious relic of martyred beings. In the process, Pompeii is reconstituted as not just a commodified tourist destination but also an active archaeological site and a pilgrimage of cataclysmic human loss.

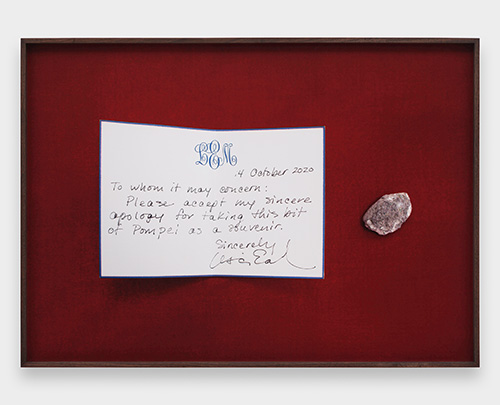

By lavishly photographing the returns as archival objects and presenting them as if they were a collection, Salane constellates them as evidence of a cultural pattern begging for anthropological interpretation. While some letters express fear of a curse, others say nothing explicit about magic (fig. 3). Yet were it not for the magic of contagion that gives any souvenir its value, no one would have stolen these items in the first place: this ostensibly inert matter was always already enchanted.

In a triumph of found art, executed with ethnographic precision, Salane reanimates these returns to show Pompeii’s power to act at a distance through magical materiality. A common quality of magic is the amplification of intentionality. Just as the thieves rediscover the intentions of archaeologists who preserved Pompeii and, through them, the intentions of the ancient people who built and lived in the ill-fated city, so, too, do Salane’s artworks isolate and amplify their intentions. What do they tell us about modern material culture more broadly?

Another common quality of magic is taking something without warrant. The flagrantly illegitimate theft of objects from Pompeii may have made these thieves particularly susceptible to magical retribution. But aren’t we all, as consumers, a bit like tourists bumbling through life’s attractions, collecting trinkets whose true provenances might horrify us? What guilty conscience resides in any of the things that we possess? What expiation do we owe for our belongings?

The enchantments of capitalism strip our manufactured surroundings of indexical associations, usually filtering out signals of woundedness that sometimes still trickle tenuously through. The small rites of restitution that Salane depicts reflect a capacity for responsiveness to those signals and resistance to the spiritual deadening of consumerism. Perhaps, these images seem to say, the materiality of magic can guide us to reparative practices of making amends—however imperfectly—for all that we’ve improperly claimed as our own.

“For a true collector,” writes Walter Benjamin, “the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of his object.”1 To practice the magic of repair on a civilizational scale would require a magic encyclopedia for all of creation, not just a few particularly precious (or particularly disgraceful) objects. With these photographs, Salane—an artist whose very medium is the magic of collection—reveals the conditions of possibility for composing such a work.

Graham M. Jones

Graham M. Jones is professor of anthropology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

I am grateful to Rose Salane for generously discussing her work with me and to Seth Riskin for further conversation.