This review appears in West 86th Vol. 31 No. 2 / Fall–Winter 2024

Exhibition:

Otti Berger: Stoffe für die architektur der moderne

Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin

MARCH 15–AUGUST 24, 2024

Catalogue:

Otti Berger: Weaving for Modernist Architecture

Judith Raum, ed.

Bauhaus-Archiv/Hatje Cantz, 2024

352 pp.; 447 color and b/w ills.

Cloth $65/€50/£50

ISBN 9783775755009 (in English; also available in German)

When it comes to sensible, thoughtful scholarship on the Bauhaus, one can rely on the Germans. It is their history and they take it seriously. Anglo-American historiography has so distorted the character and reputation of this college over the last century, that it is a relief to come across publications from Germany that attempt to redress the prevailing assessments into something approaching a sense of balance. This distortion is perhaps most obvious in the recent “rediscovery” of Anni Albers by art historians, lifting her out of the Bauhaus craft environment to a lofty position on the Olympus of fine art. In the last decade, there has been a torrent of books and exhibitions elevating this undoubtedly gifted designer’s work as the key to a new understanding of textiles as a medium for insight into the conditions of modernist art. This year alone, there have been five separate exhibitions devoted to her work (in Austin, Brussels, Nashville, New York, and Washington, DC). Last year, the major exhibition Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction opened at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art before traveling to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It hardly needs saying that the poster image was a piece by Anni Albers. In 2018–19 Tate Modern in London held a retrospective exhibition, promoted with the strapline, “Anni Albers combined the ancient craft of hand-weaving with the language of modern art.” Design historians are reduced to rolling their eyes since many of these observations have been part of the discourse on modern design for decades.

As early as the 1960s, Walter Dexel warned against the blanket association of the Bauhaus with the modern movement in design, highlighting the fact that the college had many contradictory tendencies, some of which might be taken to be anti-modern. What made it innovative, he suggested, was the very confusion that required faculty and students to negotiate different practices, but the downside was an environment that rarely, if ever, achieved the lofty aims of “a new unity” between art and industry. Despite Dexel’s critique, historians still tend to promote the simplistic view that the Bauhaus was the most important art and design college in Weimar Germany and the cradle of the modern movement. This is generally repeated without any awareness of the pattern of art and design education in Germany in the years following the World War I. Ironically, it was Hans Wingler, whose collection of documents on the Bauhaus did so much to canonize the college, who undertook the broad-based research on design education throughout Weimar Germany. His conclusion was that the 1920s was a period of intense and wide-ranging reform, giving rise to several innovative approaches to design education in cities like Frankfurt, Magdeburg, or Breslau. Far from being a uniquely innovative college, the Bauhaus was one of several centers of radical innovation, but the masters from these other colleges either went eastward or remained in Central Europe during the Nazi period, many in secluded isolation, which prevented them from exerting any influence on the English-speaking world. It is no accident that we are very familiar with the work of László Moholy-Nagy, Herbert Bayer, and Josef and Anni Albers, because they all transmigrated to leading positions in the United States. We know less about figures like Max Burchartz, Ernst May, or Ruth Geyer-Raack.

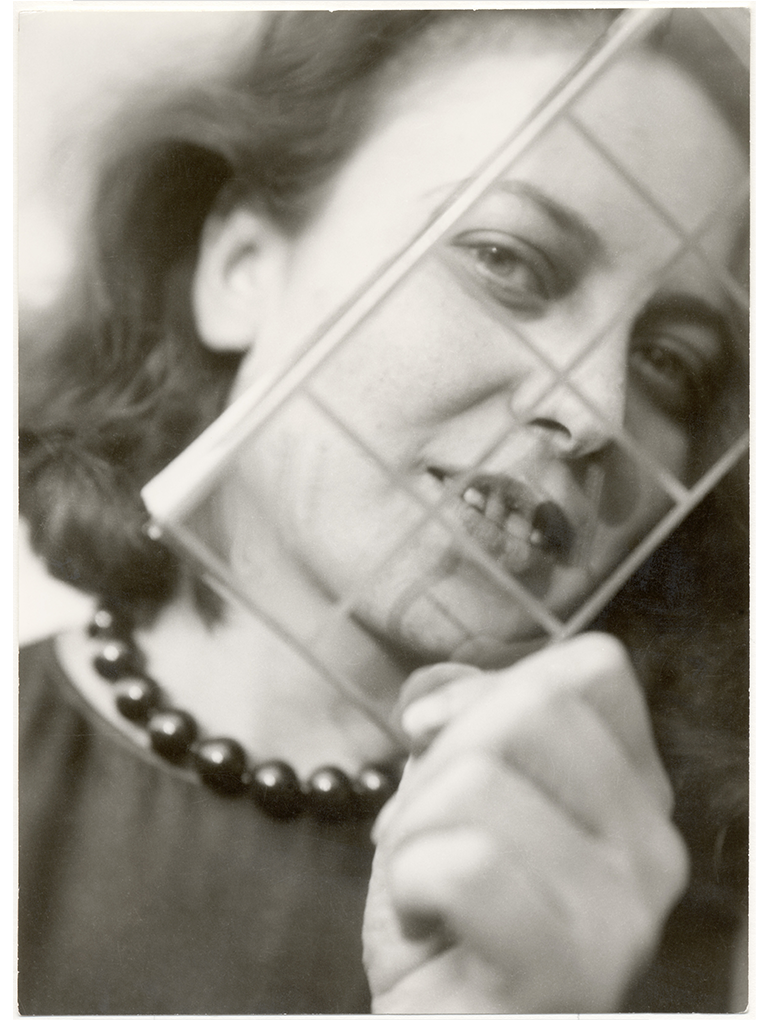

What makes the current exhibition at the Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin most effective is that it does shift the narrative, revealing the central and innovative role of Otti Berger (1898–1944), the weaver who, more than any of her colleagues in the Bauhaus, sought to apply the principles of the new design vocabulary to industrial materials and processes. Born in the Baranya region of Austria-Hungary, now part of modern Croatia, she and her family benefitted from the relatively liberal regime for educated Jewry in the Empire. Having studied textile design at the Royal Academy of Arts and Crafts in Zagreb, in 1926 she enrolled in the Bauhaus where her innovative approach was soon recognized. By this time, Gunta Stölzl had begun a radical reorganization of the weaving workshop, raising the technical standards, shifting the focus to new materials, especially synthetic fibers, and, in the process, pushing out Georg Muche, the form master who had never really had much sympathy for textiles in any case. Berger was the student who most fully embraced these ideals, taking a special interest in fabrics for new purposes, such as upholstery, wall coverings, and insulation for trains, airships, and public spaces. These applications presented different challenges as to how textiles might perform, how they dispersed light, control heat, and influence the surrounding atmosphere, especially in contexts like public transport and waiting rooms where there was heavy use. This was the type of work she became known for after setting up her own design studio in Berlin in 1932. She was also very innovative in building her career, promoting her work through exhibitions and magazines operated by the various werkbunds notably in Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Sweden, and the Netherlands, as well as in Germany itself. Berger pioneered the registering of legal patents for her designs, licencing a number of factories across Europe, such as CE Baumgärtel & Sohn in Lengenfeld, Saxony, De Ploeg in the southern Netherlands, and Helios in Bolton, Lancashire, United Kingdom. There is a popular view that Britain was unsympathetic to the continental modern movement in design, but Berger had several supporters in the United Kingdom, notably the weaver and educator Ethel Mairet who translated Berger’s remarkable 1930 essay “stoffe im raum” (fabrics in space). In fact, Berger moved to Britain in 1937 when her position as a Jew in Nazi Germany became intolerable. However, her difficulties with the language, compounded by her deafness, and her failure to obtain emigration papers to the US to join her fiancé, the architect Ludwig Hilberseimer, meant that she could never quite settle or even feel secure. In 1938 she returned to Yugoslavia, from where she and her family had been deported, to care for her mother. Berger was murdered in Auschwitz in 1944.

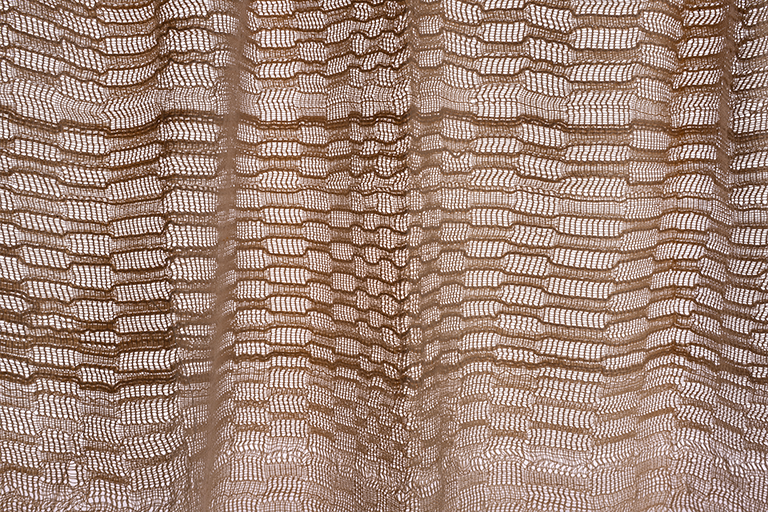

In some respects, this poignant and tragic end has come to define Berger in the literature on the Bauhaus and in broader accounts of the Weimar cultural diaspora. However, Judith Raum, who curated the exhibition and edited the book under review, clearly wanted to shift attention back to Berger’s design work, especially that from her years as an independent designer in the 1930s. This has been a difficult task since Berger’s work has never been collected systematically. As a result, there are examples dispersed in various museums and private collections across the world with only a vague indication of the overall range and character. Quite recently, a suitcase of pieces was discovered in London, having been left behind in 1937, but it had no documentation and remains uncatalogued. To overcome some of these obstacles to a clearer picture of the designer’s career, Raum took a deep dive into Berger’s weaving techniques, attempting to identify her materials, the type of weave she employed, and the function of the textiles. Raum has stated that she wanted to follow the logic of the weave, not necessarily the chronology. This has allowed her to study the combinations of different fibers and, in close collaboration with Katja Stelz, to re-weave several fabrics, revealing the complexity of finished pieces that appear disarmingly simple. The exhibition and the book can be seen as complementary in this process of investigation; the exhibition includes handling sections to reveal the tactile qualities of the textiles, while the book places great emphasis on the photography to capture the exact features of each design and swatch. In some cases, the textile samples were suspended on specially designed frames and backlit for the photographs to reveal the different effects. The combined achievement is to produce as near a comprehensive introduction to Berger and her work as might be possible at the moment.

Beyond this overall coverage of Berger’s mature work, what the Bauhaus-Archiv exhibition also revealed is the contrasting tendencies in industrial practice, interior design, and modernist textile design in the interwar period. For Berger, woven textiles employing modern fibers had to be experienced from multiple senses, appreciating the texture, tactility, wrapping, stretching, covering, and any number of other faculties that the material may utilize. For Berger, this was the new frontier of modern textiles, a multi-sensorium that had numerous applications in our everyday lives, not merely the revelation of abstract form within the weave. For those who cannot see the exhibition and will be unable to feel the sensation of Berger’s different fibers in one’s fingers, the book offers an excellent equivalent; beautifully designed, and impeccably researched by Raum and an international team of scholars, it is a fitting tribute to one of the great modernist designers.

Charles Parley

Charles Parley is a historian and translator based in Barcelona.

Lucia Moholy (photographer), portrait of Otti Berger, ca. 1927. Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin. © VG Bild-Kunst Bonn, 2024.