Exhibition:

Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, October 13–January 26, 2025

(Also National Gallery, London, March 8–June 22, 2025)

Catalogue:

Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350

Joanna Cannon, Caroline Campbell, Stephan Wolohojian, et al.

London: National Gallery Global Limited/Distributed by Yale University Press

312 pp.; 217 color ills.

Paper $50

ISBN 9781857097160

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the National Gallery, London, have joined forces to produce an extraordinary exhibition of works from the Tuscan hilltop city of Siena in the first half of the fourteenth century. As organizers, curators from the two institutions, Caroline Campbell (curator of Italian paintings before 1500, National Gallery) and Stephan Wolohojian (John Pope-Hennessy Curator in Charge of European paintings, the Metropolitan Museum), are joined by an art historian with a long-term interest in Italian art of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Joanna Cannon (professor emerita, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London). It is hard to imagine a more appropriate scholarly team for such a project. The result in the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum is not only a breathtaking spectacle but a carefully argued demonstration of the place and development of luxury artifact production in Siena prior to the devastation caused by the bubonic plague between 1346 and 1353. The generously illustrated catalog contains essays by thirteen scholars in addition to those by the curatorial organizers.

The exhibition opens with a trio of objects cleverly selected to illustrate the currents that fed into artifact production—specifically painting—in fourteenth-century Siena. All represent the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child. Flanking the 11 by 8 inch gilded and painted panel by Duccio di Buoninsegna (ca. 1255–before 1319), bought by the Metropolitan Museum in 2004, is a Byzantine icon from the church of San Niccolò al Carmine, Siena, known as the Madonna del Carmine (Ministero del Interno, assigned to the Museo Diocesano di San Bernardino, Siena), and a small French carved ivory statuette (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Cloisters Collection). The silver relief embellishments applied later to the Byzantine icon to honor its sacred efficacy have been detached but are displayed beside it. The art historical implication of the juxtaposition is that the Sienese painter melded the stylized and impersonal qualities of the Byzantine icon with the humane specificity of the French sculpted group to produce a devotional item that combines divine authority with humanity. This is a fitting introduction to the arguments presented with care and sensitivity in the galleries that follow.

Notably, the juxtaposition of the Byzantine icon, the Duccio devotional panel, and the French ivory statuette does not rely on painting alone. Despite the title of the exhibition, this show is about artifact production in a wide variety of media. Although devotional paintings by Duccio, the brothers Pietro (active by 1306, died ca. 1348) and Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1285–ca. 1348), and Simone Martini (ca. 1284–1344) provide an armature for the argument, the organizers have set them beside illuminated manuscripts, metalwork, stone and ivory carvings, enamels, and—most revealingly—textiles. Indeed, the comparisons across media that the organizers invite, as well as the frequent presentation of works in the round rather than against walls, are meant to show painted and gilded panels as the three-dimensional objects that they are. Such panels are no less three-dimensional than are a sculpture, an ivory box, or an archbishop’s crozier.

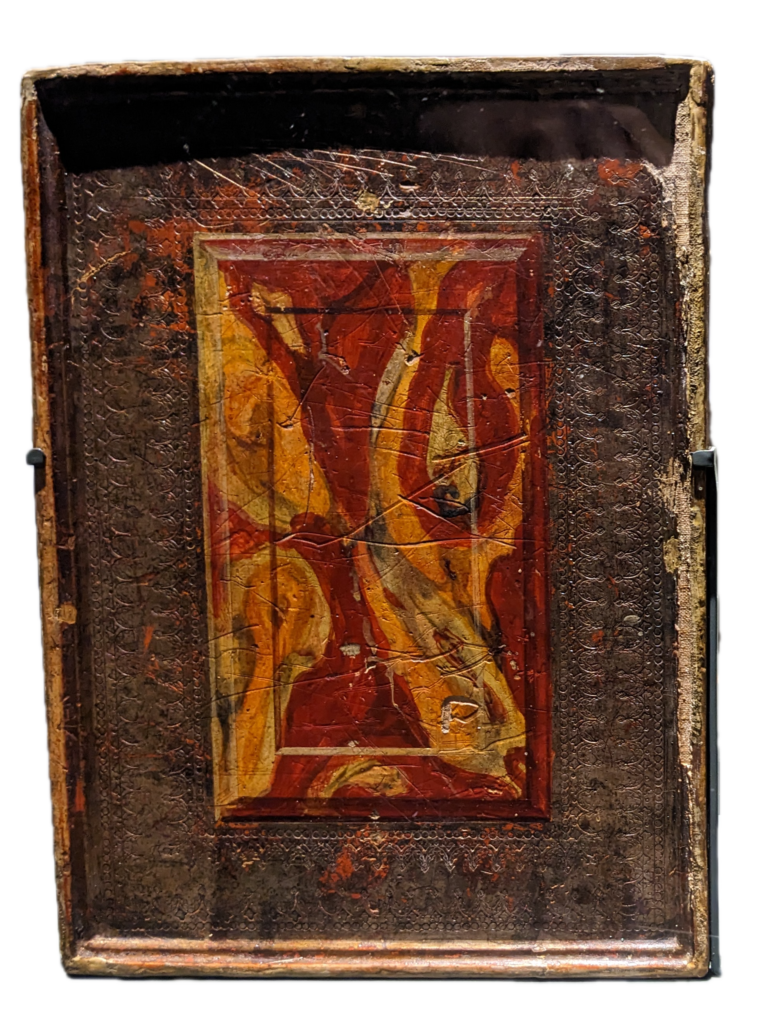

The backs of certain small panels intended for personal devotion are often as arresting as the scenes of Christ and his saints on the fronts. This is so in the case of those versos painted in trompe l’oeil to resemble sheets of porphyry or colored marble. Three panels by Pietro Lorenzetti depict such surfaces in various colors, each as though beveled and set in the middle of a field framed by decorative punchwork. The plaques are painted to give the illusion of light falling on their surfaces from the upper left. Two are from a series originally of at least four hinged panels representing scenes from the Passion of Christ: Christ before Pilate (Musei Vaticani, Vatican City), and The Crucifixion (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). The third such panel by Pietro Lorenzetti is one half of a diptych representing the Man of Sorrows. Its striated yellow, green, and red fictive marble plaque framed by punchwork is yet more elaborate than those painted on the versos of the Passion panels. The verso of its other half, the Virgin Mary and Christ Child, has been stripped to the bare board. Both halves of this diptych are from the Lindenau Museum, Altenburg. The verso of a small panel representing Christ Discovered in the Temple by Simone Martini (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) similarly is a trompe l’oeil rendition of a framed and beveled dark red and black flat stone plaque. It is disfigured by a wax seal, two labels marking its inclusion in the celebrated Art Treasures of Great Britain exhibition held in Manchester in 1857 (possibly the largest art exhibition ever mounted), and the exhibition of Old Masters at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, in 1881. The surface is chipped and damaged. The presence of such labels is a testament to the art historical bias that lends privilege to the assumed focus of attention—the picture on the recto of the panel—alone. The organizers’ decision to acknowledge the objecthood of these items, even if it means exposing the prejudice of their predecessors, is laudable. However, inexplicably, only one verso is illustrated in the catalog: the coat of arms of Hainaut-Holland on the so-called “Sachs Annunciation,” described as possibly by a French or Franco-Flemish painter (Cleveland Museum of Art), discussed by Dillian Gordon—and it is not even in the exhibition. These omissions suggest that an acknowledgement of such small, portable devotional objects designed to be manipulated and viewed from every angle only goes so far.

Despite excellent decisions of selection, juxtaposition, and display, some choices raise serious questions. Not all of these are necessarily the responsibility of the curatorial organizers, for such initiators never make every decision on their own. The first concerns the design of the exhibition. Stylized rectangular columns and walls painted to resemble dark pietra serena evoke a Tuscan church interior. This is broadly appropriate, given that many—though far from all—of the items on display originally had a setting both devotional and liturgical, and some still do. However, overriding this evocation is another, somewhat less fortunate one. The galleries resemble not so much a church interior as a magnified art fair booth where the strong spotlighting and weak ambient lighting is calculated to flatter rather than to illuminate forensically the works on display. The effect is dramatic, and in a certain sense evocative of altarpieces in situ in Italian churches—at least as one sees them after feeding coins into the slot of a timed light switch box—but I could not help expecting an art dealer to emerge from the shadows to make a pitch. The apparatus of commercial seduction seems at odds with the dispassionate examination and informed aesthetic appreciation of such works.

The second cause for concern is the vulnerability of the painted and gilded panels. Some years ago, there was a consensus among museum conservators and curators that hygroscopic wood panels—objects that warp in response to changes in humidity—should never travel. The elaborate apparatus supporting Pietro Lorenzetti’s monumental polyptych representing the Virgin Mary and Christ Child flanked by various saints known as the Pieve Altarpiece—screwed wooden batons and a large metal armature—may prevent cracking as panels strain against these elements designed to inhibit movement. Or they may not. Is the risk to these irreplaceable items justified? I am prepared to be reassured by conservators who may have reassessed those risks, both in general terms and for individual works, but that reassurance would have to be tempered by an acknowledgement that the history of conservation is one not only of skilled achievements but also of costly errors.

The third cause for concern is more conceptual. Again, the organizers are not invariably responsible for every decision in this respect, so the art historical bias inherent in the title of the exhibition—The Rise of Painting—is not necessarily theirs or theirs alone. That phrase implies that what visitors see is most valuable for its pretended status as the first (or at least an early) step in an evolutionary development of one art form—painting—that implicitly extends from Duccio to Picasso and beyond. That is, a good part of the value that those responsible for the exhibition invite viewers to ascribe to the paintings on view is a retrospective validation in the light of subsequent developments, developments exemplified in many other neighboring galleries in the two organizing institutions. It seems likely, though, that the painted objects, whether large altarpieces or small devotional panels, have a far more urgent affinity with items in other media made at much the same time than with painting as conceived in standard European art history. This implication—that painting is a stand-alone practice separable from other modes of making—is not necessarily what the organizers intended, but more effort is needed than is shown here to affirm painting as no more important than, say, textile making while also exhibiting the particularity of the qualities that make attention to the painted objects concerned so worthwhile. Furthermore, the character of the available painted objects—that they be moveable even when large—implies that painting in fourteenth-century Siena was exclusively for religious purposes. There was also secular painting in Siena, though the most prominent example of a secular painted scheme is immovable. This is Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s much debated Allegory of Good and Bad Government in the Sala dei Nove (council chamber of the city’s executive magistrates) in the Palazzo Pubblico. Ambrogio Lorenzetti executed these six scenes in fresco, so they remain in situ: a still salient reminder of the benefits and perils that governments can impose.

A fourth, even more challenging issue is also conceptual. All these works have functioned, and some continue to function, within a belief system that is unfamiliar to many of those who might be its distant cultural heirs, and baffling to others to whom that belief system is wholly foreign. To any number of visitors, the entire apparatus that gave rise to these items is foreign. A towering wooden atingting kon (slit gong) from Ambrym Island, Vanuatu, introduced into one of the galleries of this exhibition might pass unremarked by many as not out of place. The Metropolitan Museum has a splendid example carved by Tin Mweleun in the mid- to late 1960s. For the staff of the Metropolitan Museum, the slit gong is an artwork no less than is Pietro Lorenzetti’s monumental polyptych, the Pieve Altarpiece in the exhibition. Yet that altarpiece still functions devotionally and liturgically in the church of Santa Maria della Pieve in Arezzo. Like the Ambrym slit gong, it is far more than an artwork. To treat fourteenth-century Sienese painted and gilded panels as no more than artworks is, however, a different matter from treating the slit gong as an artwork, because the ruling assumption within the museum is that the former is an artwork self-evidently. Yet both the slit gong and the altarpiece are subject to the process known in analytical philosophy as artification whereby an item “is changed into something art-like.”1 But being subject to artification is insufficient to account for the qualities of both kinds of items. Both Tin Mweleun’s Ambrym slit gong and Pietro Lorenzetti’s Pieve Altarpiece ideally require forms of attention and explication in addition to artification. This does not mean that all aspects of either can be made apparent in any one set of circumstances. It is fair to attend to only one set of qualities of either—such as those that result from artification—but what is worrying is that in the case of the Sienese painted and gilded panels the organizers unreflectingly assume their status as artworks and this status takes implicit precedence over any other status they may have. This is an example of what we might call structural Eurocentrism, and its effects are pernicious, as thinkers from Vanuatu and elsewhere in Oceania (and not only in Oceania) can attest.

One way to counter structural Eurocentrism is demystification, and one way to demystify such items as these Sienese panels is to show them in the round—as the organizers commendably do—and as human-made artifacts. Yet there is little sense in this exhibition of their constituent materials—wood (usually poplar), linen, animal glue, gesso, gold leaf, egg yolks, pigments—or how artisans worked them. Of particular interest is the punchwork in many gilded areas. Makers used metal punches made by engraving, drilling, and filing. The maker holds the punch perpendicular to the gilded surface and strikes it lightly but decisively with a hammer. If executed well, the blow indents the still flexible ground without penetrating the gold leaf. Makers could thereby create intricate patterns. The value of the punches was such that they were kept in individual painter’s workshops, only occasionally changing hands by sale, gift, or inheritance. This means that the punchwork on any individual painting is usually characteristic of a particular workshop.2 An exploration of this practice, the results of which viewers could hardly help but notice on both the rectos and versos of many of the painted and gilded artifacts in the exhibition, would help to demystify them. But such gilded elements are not painted, so perhaps the organizers decided to ignore punchwork because to draw attention to it might be a distraction from the purely painted elements of the artifacts.

Despite these reservations, this exhibition is a huge achievement. It gives visitors an extraordinary opportunity to immerse themselves in a variety of products made during a long half century when Siena was a medieval republic dominated by a commercially oriented noble elite that profited not only from wool production and trade via its Mediterranean ports to its west, but also from money lending. It had defeated its rival city state, Florence, at the Battle of Montaperti in 1260. It retained its prosperity—for its elite—until the disaster of the mid-fourteenth-century bubonic plague. Thereafter, internal dissentions and political instability led to the republic’s decline. The items on view are byproducts of pre-Black Death prosperity. The vibrantly colored carved and painted panels with their lavish gold backgrounds still shine, but, as this exhibition demonstrates, non-painted items can command equal attention, upsetting the Eurocentric art historical hierarchy that promotes painting and demotes the so-called minor arts. Viewing these wonderful exhibits, I half-expected to hear the distant drums of a contrada, or city ward, procession echoing through the tangled streets of the hilltop city. The evocative setting and its contents brought not only frustrations but seductive stimulation.

Ivan Gaskell

Ivan Gaskell is professor of cultural history and museum studies at Bard Graduate Center, New York.

- 1 Ossi Naukkarinen and Yuriko Saito, introduction to Contemporary Aesthetics Special Volume 4, Artification, ed. Ossi Naukkarinen and Yuriko Saito, 2012: https://contempaesthetics.org/newvolume/pages/journal.php?volume=49

- 2 Ivan Gaskell, “After Art, Beyond Beauty,” in Inspiration and Technique: Ancient to Modern Views on Beauty and Art, ed. John Roe and Michele Stanco (Oxford and New York: Peter Lang, 2007), 311–34 with further references.